Paleobiologist Dr. Kenshu Shimada has been fascinated by fossil sharks, including the giant Otodus megalodon, since childhood — he found his first megalodon tooth at 13 years old.

Exactly how large megalodon was in real life is a long-standing mystery — no complete fossils have ever been discovered. But now, to Shimada’s own surprise, his most recent research suggests megalodon could have reached a whopping length of 24m.

“Megalodon is not a simple, gigantic version of great white shark. I think that we really have to move away from that concept,” said Shimada, a professor of biological and environmental sciences at DePaul University in Chicago who served as lead author.

The findings could help reshape how scientists and popular science fiction depict the enormous creature — and has possibly shed light on what lets some marine vertebrates evolve extraordinarily huge proportions, according to Shimada.

Megalodon fossil record: Plenty of teeth but not much else

Unlike in The Meg, the prehistoric megalodon never coexisted with humans, but between 15 million and 3.6 million years ago, the apex predator dominated oceans around the world, according to various megalodon fossils scientists have unearthed.

“On the other hand, teeth are very hard, so they’re durable.”

Megalodon produced new teeth throughout its life, helping make these fossils a fairly common find.

Neither shark backbone specimens were found with the massive, serrated teeth associated with megalodon, but scientists have presumed they belong to the same species.

“We kind of realised — click— that (the) great white shark is not a good model,” Shimada said. So, he began searching for a better match for megalodon’s modern analogue.

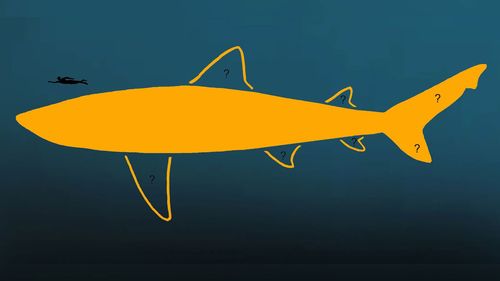

Megalodon may have had a long, sleek body

Shimada and his team compared 145 species of living sharks and 20 species of extinct sharks and built a database of the proportions of their heads, bodies and tails. The researchers then compared these proportions with the parts of megalodon’s body that have been found.

“We have a vertebral column that’s known, and if we assume that that’s the complete trunk length, then why can’t we estimate the head length and a tail length based on modern day?” Shimada said.

The researchers calculated that the likeliest body plan for megalodon wouldn’t have been that of a stout, tank-like great white but rather a more streamlined fish, such as a lemon shark. In this discovery, Shimada said, his team also stumbled upon a larger pattern in marine biology.

“If you stay in a skinnier body, there is a better chance of being able to grow larger,” Shimada said. This principle applies to megalodon, which according to Shimada’s new study could have been up to 80 feet (24m) long, but thinner than previous models.

Dr Stephen Godfrey, the curator of paleontology at the Calvert Marine Museum in Solomons, Maryland, who was not involved with the study, said he was surprised by both megalodon’s proposed similarity to a lemon shark and by the giant size proposed by Shimada and his team.

Unprecedented sighting of monster-looking deep-sea predator

“The argument that they make, that a long, slender animal that size is more hydrodynamically efficient than if they’re really kind of fat and chunky, like if you scale up a living great white — that argument is a good one,” he said.

“But still, I’m not saying it gets stuck in my craw, but wow. I mean, that’s twice the size,” Godfrey said, referring to the estimated megalodon length increasing from 50 to 80 feet.

Ultimately, there’s just one way to know for certain how long megalodon was and what it looked like.

“What we really need is the discovery of the complete skeleton,” Shimada said.

“The real test comes when we really have the complete skeleton, and then it will support or refute whether it was really skinny or stocky.”