If the First World War marked Canada’s emergence as a more independent nation, the Second World War showcased its ability to exceed expectations on the global stage. Canadian fighter aces and air crews defended the UK during the Blitz, while our sailors and merchant navy helped turn the tide in the Battle of the Atlantic. Canadian troops drove the Nazis from Italy, stormed Juno beach during D-Day, and slogged through muddy, flooded fields to liberate the Netherlands. By V-E Day – Victory in Europe – our allies saw us as equals.

But that was eight decades ago. Today, as authoritarian regimes challenge Western democracies, the echoes of past conflicts resonate. Decades of neglect have left Canada’s military a shadow of its former self. This special three-part series delves into Canada’s pivotal role in the V-E Day victory and examines the current state of our armed forces, offering insights on how Canada can reclaim its stature in national security and defence. Parts 1 and 2 set the scene, while Part 3 brings the conflict into focus for Canadians today.

Part 1: Prelude to valour – Canada’s path to war

By J.L. Granatstein

The war against Nazi Germany ended with the German capitulation on May 8, 1945. Eighty years ago, Captain Harry Jolley, the dental officer with the 12th Light Field Ambulance in the 4th Canadian Armoured Division stood on German soil when the surrender came into effect, and he wrote home that “none of us shouted, threw hats in the air, nor anything of that sort.” He went on to say “I felt – I don’t know practically nothing… we’re tired – physically & emotionally… our sense of balance is a little out of kilter. Death, dirt, destruction – human & material – have become so commonplace.”

Jolley had enlisted in 1940, served in Canada, England, North Africa, Italy, and Northwest Europe. He had grabbed a weapon and helped his unit’s Advanced Dressing Station drive off a German attack in the Hochwald in April 1945, and he personally led stretcher bearer parties clearing the street of casualties. Jolley had hoped (wrongly) that he might receive a gallantry medal. Instead, he was promoted to major, mentioned in despatches, and made a member of the Order of the British Empire. At V-E Day, Jolley was, much like all those men who had fought in the war, exhausted. Everyone, including those at home who had worried about their men and women overseas and worked in the fields and factories, was tired. Five-and-a-half years of war and strain was too much.

***

Canada in 1939 was caught in the tenth year of the Great Depression. Unemployment remained high in a land without welfare except charities and small amounts of public moneys. The country of 11 million people produced a Gross National Product just north of $5 billion, but it had a small manufacturing base and tariff walls limited its trade with the world. Canadians had fought valiantly in the Great War two decades earlier, but all that remained in 1939 were memories of the valour of the 65,000 dead. The military had just ten thousand regular sailors, soldiers, and airmen, untrained and ill-equipped reserve forces, and almost no modern equipment for the army, navy or air force.

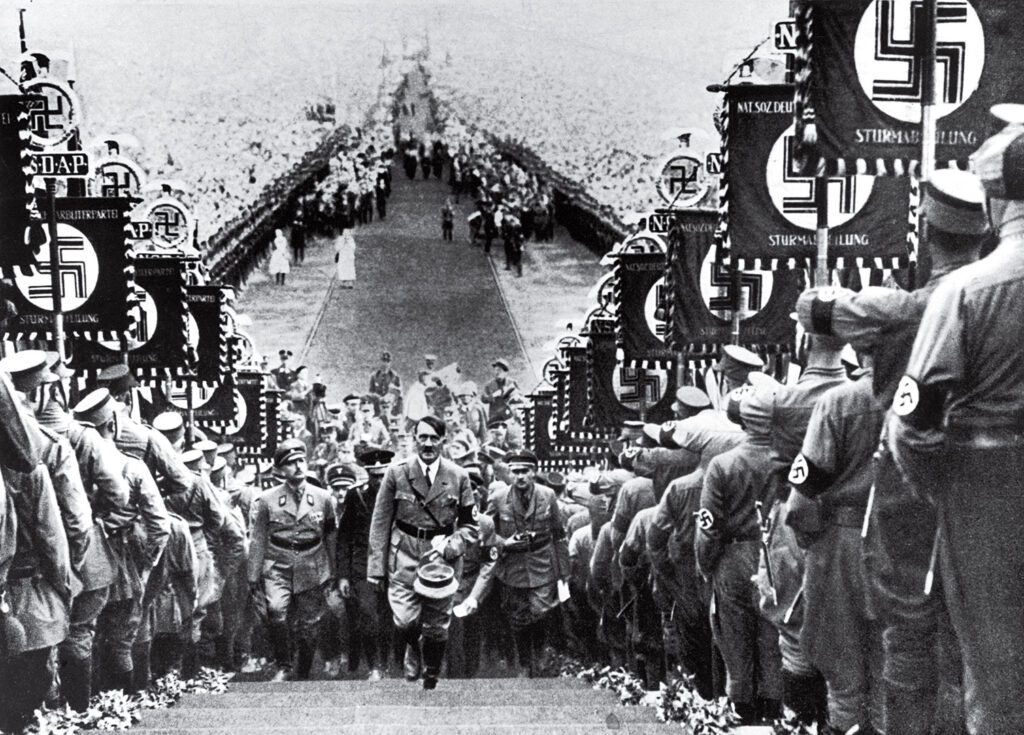

Prime minister William Lyon Mackenzie King had been in power since 1921, the first five years of the Depression aside. Lacking charisma, but intelligent and politically shrewd, King intended to keep the country’s francophones in his Liberal party. To King, that meant making no commitments to go to war with Germany if Britain did. “Parliament will decide,” he said repeatedly, and if appeasement could be made to prevent war, King was for it; if not, King understood that Canada must be at Britain’s side, something Anglo-Canadian elites and most of the English-speaking population would demand. In any case, whatever happened, there would be no conscription. That had sharply divided Canada in the First World War, enraging Quebec, and King (and the Conservative leader, Dr. Robert Manion) pledged in March 1939 after Adolf Hitler’s Germany swallowed Czechoslovakia that Canada would not impose compulsory overseas service if war occurred.

By August 1939, war seemed inevitable. On the 23rd of that month, Hitler and Soviet leader Josef Stalin signed a non-aggression treaty – with secret clauses dividing Poland and giving the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) a free hand in Finland and the Baltic states. They signed the pact despite being enemies – each side a dictatorship with one Nazi and the other Communist.

Germany invaded Poland on September 1. Britain and France did not want to fight, but both declared war on September 3. London expected its Dominions – Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa – to dutifully come along, but Canada held back… for one week. King’s pledge that Parliament would decide had to be honoured and it was – only a handful of MPs voted against joining the fight. Given the simmering opposition to war in Quebec, King had maneuvered skillfully to bring a more or less united nation along with him. Canada declared war on Germany on September 10.

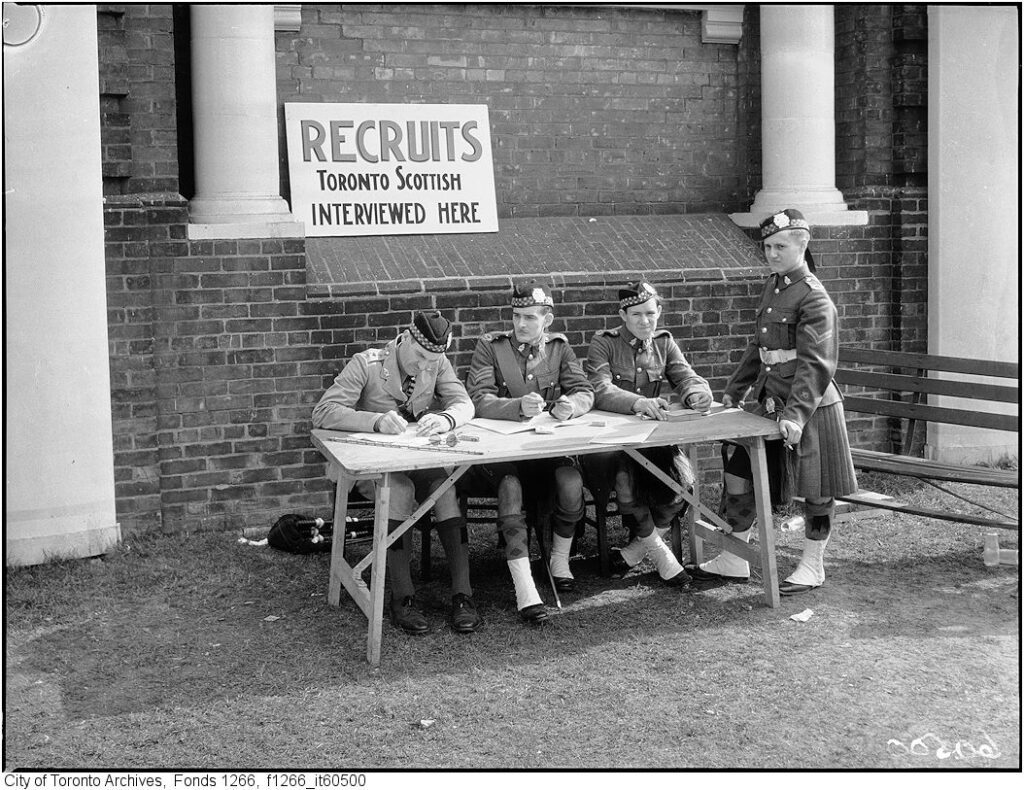

But what would Canada do? The government lacked funds, and its military had very few men – 455 regular army officers, for example, at least half of them too old or too ill for overseas service – and little equipment, and the bloodletting of the Great War had muted the public’s enthusiasm for another conflict. King believed that Canada had only a “limited liability” responsibility and he didn’t want to send even a single division overseas, but his Cabinet disagreed. On September 19, the Prime Minister announced Canada would raise two divisions, with one proceeding overseas when ready.

Six days later, Premier Maurice Duplessis dissolved the Quebec legislature and called an election, framing it as a retort to Ottawa’s attempt to destroy the province’s autonomy. Duplessis railed against “une campagne d’assimilation et de centralisation” – but in reality, he was furious about the declaration of war.

In response, the King government and his Quebec ministers launched a campaign against Duplessis’ Union Nationale, repeatedly promising that there would never be conscription. Duplessis lost badly, and a more friendly Liberal provincial government assumed power in Quebec City.

Ironically, in mid-January 1940 King faced another political challenge – this time from Ontario Liberal Premier Mitch Hepburn, who, in calling a provincial election, denounced Ottawa for not prosecuting “Canada’s duty in the war in the vigorous manner the people of Canada desire to see.” The Prime Minister seized on this challenge to suddenly call a federal election for March. Catching the Conservatives, the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation, and Social Credit off guard, King swept to a sweeping majority. Hepburn won as well, but King’s victory neutralized criticism of the war effort.

In truth, neither Duplessis’ claims of assimilation and centralization or Hepburn’s claims of a lacklustre war effort made sense. Ottawa had centralized nothing, assimilated no one. Nor could anyone have realistically expected Canada to move from a tiny military to war-fighting capabilities in only a few months. Troop training had only begun. Canada’s handful of naval vessels were busy guarding convoys to Britain, and the Royal Canadian Air Force had only 4,000 personnel and a few modern aircraft and airfields with which to train new pilots. But this was already about to change.

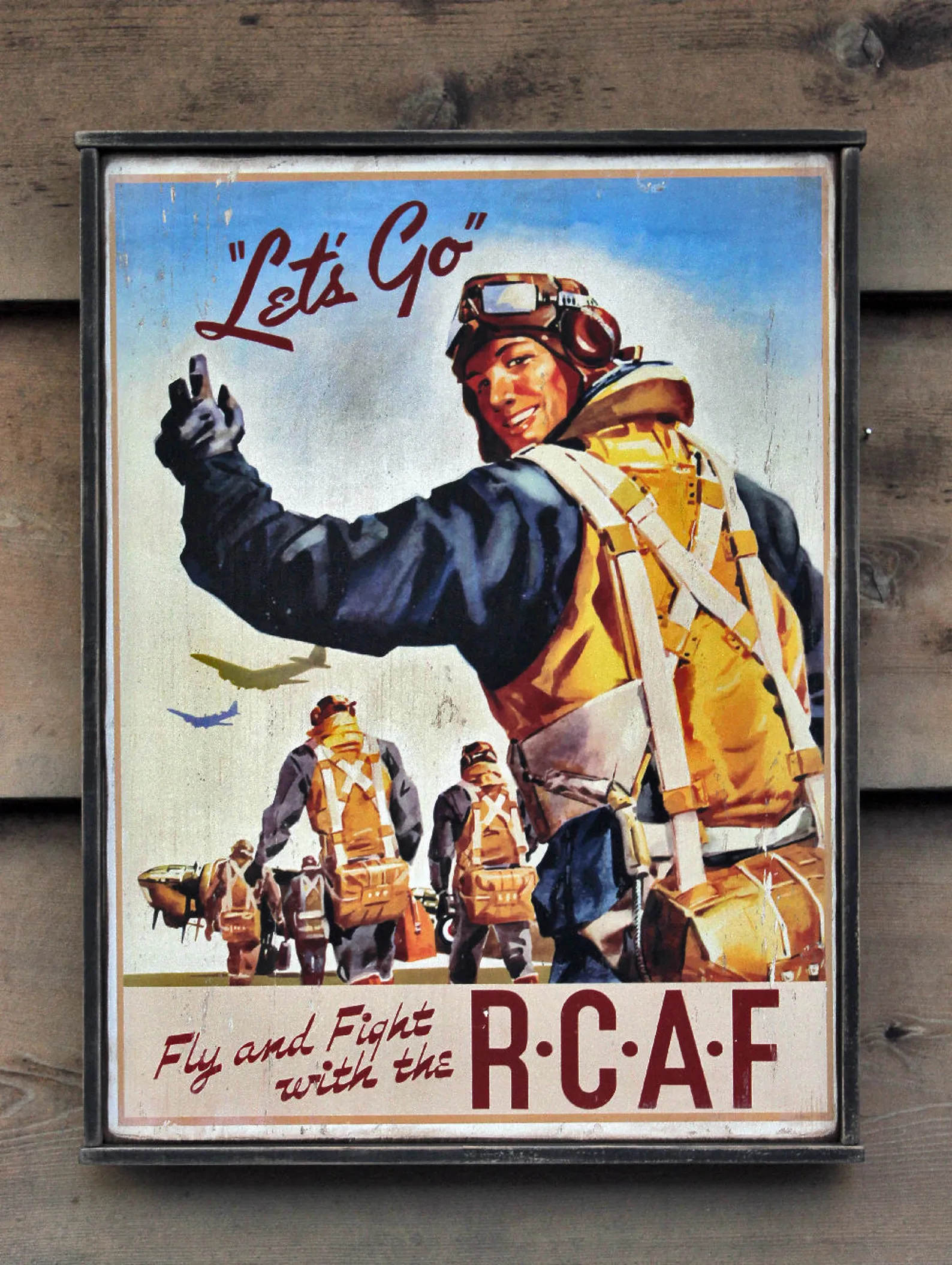

On September 26, Britain asked if Canada would run a major training program, what was to become the British Commonwealth Air Training Program. The request, which came a week after the announcement that an infantry division would be dispatched overseas, upset King: “It shows how quite unprepared the British… were in their plans…,” King told his Cabinet. Weeks of hard and acrimonious negotiations with a British team followed. On December 17, Mackenzie King’s 65th birthday, the federal government announced the plan. The BCATP became a huge operation, with US President Franklin D. Roosevelt calling Canada “the aerodrome of democracy,” as it built 151 training stations and airfields across the country and ultimately produced 131,533 aircrew, more than 72,000 of whom joined the RCAF. The program ultimately cost $2.2 billion, of which Ottawa provided $1.6 billion, sums that would have seemed inconceivable in 1939.

Ottawa in the Second World War also learned from the Great War experience with war finance. The King government ran two war loans and ten Victory Bond campaigns and raised $12.5 billion, a quite extraordinary $550 per person, with businesses and corporations accounting for half of the funds raised. Moreover, the King government did not flood the nation with currency and spur out-of-control inflation as in 1914–18. In the Second World War, wage and price controls held down inflation very successfully.

The outlines of Canada’s war effort were thus in place early in the conflict. The Liberal government firmly controlled the situation, and faced a weak Opposition in Parliament. Canadian troops were en route to Britain, the RCN was hunting U-boats in the North Atlantic, and the RCAF, while beginning to dispatch pilots overseas, was running the BCATP. It may still have been a limited liability war in Mackenzie King’s mind, but that was about to change very dramatically.

***

The German army had invaded Poland and, despite strong Polish resistance, soon took Warsaw and met up with the USSR’s Red Army which, in accordance with the treaty signed in late August, moved west into the Polish countryside. Britain and France, Poland’s allies, had been unable to help stave off its defeat and occupation.

The war then settled down into what came to be dubbed the “phoney war.” The Allies and Nazis both built up their defences in Western Europe, but Hitler had plans. In April 1940 he subdued Denmark in a day and seized the Norwegian capital of Oslo. Britain and France sent troops to Norway, but they were outfought and out thought by the German high command.

It soon became clear that they had been out thought in Western Europe as well. On May 10, the very day that Winston Churchill became prime minister of Great Britain, the Wehrmacht and Luftwaffe launched a blitzkrieg against the Netherlands, Belgium, and France. Using surprise and employing tanks, aircraft, mechanized troops, brilliant leadership, ruthlessness, and speed, the Germans crushed all opposition. By the end of May, the British were trying desperately to save the men of their expeditionary force and France was struggling to survive. Paris soon fell and on June 22 France surrendered. Britain hung on, the miracle of Dunkirk that saved most of its trained troops (but little of their equipment) the only bright spot in a bleak Nazi-dominated Europe.

Source: Public Domain

These events struck Canada with the force of a thunderbolt. All of Canada’s destroyers sailed to British waters to assist. A brigade from the First Canadian Division in England went to France just before the surrender as Britain tried to create a new defence line; it was a hopeless effort, so the Canadians returned to England, leaving some of their equipment behind. Soon, the Second Division arrived to reinforce the British homeland.

With the possibility that Britain might be conquered Canada had to plan for its own survival. This meant a wartime alliance with the still-neutral United States, a deal sealed between King and Roosevelt in August 1940 at Ogdensburg, NY, The Permanent Joint Board on Defence effectively guaranteed Canada’s security and let it send its military resources overseas. O.D. Skelton, King’s chief foreign policy advisor, correctly said Ogdensburg “was certainly the best day’s work done for many a year.” In 1941, on a “grand Sunday” at Hyde Park, NY, the two leaders signed an economic pact that resolved Canada’s shortages of US dollars and began the integration of the two wartime economies. The war had changed attitudes in both countries and when America entered the conflict after Pearl Harbor, integration proceeded apace.

King’s nation now understood this was a war without limits, a war for the survival of freedom, and money was no object. It was also a war in which the shibboleth of conscription began to disappear. Although there yet was no shortage of volunteers for the three armed services, in June 1940 the government introduced the National Resources Mobilization Act, registering men and women and establishing conscription for home defence initially for 30 days army training. (Ottawa later extended the conscription period to 90 days and then for the duration of the war.) Major-General Harry Crerar, soon to be Chief of the General Staff, called this the “first bite at the cherry” of conscription. He was right.

In early 1942 with pressure for conscription building, King called for a non-binding plebiscite to release the government from its “no conscription” promises. The move outraged both the Conservatives and Quebec, but King swept the country 64 per cent to 36. But 73 per cent in Quebec voted “no.” Did this mean conscription for overseas service would begin? Not so, the cautious Prime Minister said to Parliament: “Conscription if necessary but not necessarily conscription.” Within two years, the government would be forced to act.

***

From a standing start in 1939, Canadian war production took off with great speed. In the first months of the war orders amounted to a mere $60 million. In 1941, production grew to $1.2 billion, more than in the whole of the Great War; in 1942, production reached $2.5 billion; and by war’s end, Canada delivered $11 billion in goods and food. It built ships in quantity, the auto industry produced some 800,000 trucks and jeeps and 50,000 armoured vehicles, and the aircraft factories turned out everything from fighters to four-engine Lancaster bombers. Crown corporations, created by C.D. Howe’s over-arching control of the wartime economy, manufactured wood veneers and synthetic rubber among many other scarce products, and Howe took control of Canada’s uranium that went into the development of the atomic bombs. Canada produced so much food, minerals and equipment that it generously and freely gave $3.5 billion in gifts and mutual aid to Britain and more to its Allies. Astonishingly there was almost no corruption.

The workers to do the wartime jobs came from across the country, men and women moving to the cities to be close to the factories. There were jobs with good wages for everyone in the war effort, including more than 300,000 women working at everything from building warships and Bren guns to driving buses, and as much overtime as people could handle. Farmers lacked help, but somehow managed to get bumper crops to market to feed Canadians and overseas populations. For the first time in years people could save or buy Victory Bonds, and if they lived in substandard housing and suffered from a scarcity of goods and the rationing of scarce foodstuff, they could at least hope that a booming economy and government plans for a better postwar Canada would improve their lives. Mackenzie King had created Unemployment Insurance in 1940, and as victory neared his government, spurred by the rise in support for the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation, offered Family Allowances – the first government money ever sent directly to mothers – a housing policy, and funding for munitions factories to convert to peacetime production.

***

Meanwhile Great War veterans, many too old for overseas duties, put on uniforms again to train the new recruits, those volunteering for service anywhere and the home defence conscripts. “What was mobilized was a mob,” General Christopher Vokes wrote later. “Officers and sergeants had a vague notion of what to do… They could probably lead a parade down the street.” That was true in the other services too. Merchant Navy officers took command of corvettes, many soon built in Canada, and fought the German U-boats with crews green as the Prairie grass from which many had come. Pilots who had battled against German flying ace Baron von Richthofen 25 years earlier took over training aircrew volunteers, and younger men formed Canada’s first fighter squadron in Britain, participating gallantly as the Luftwaffe launched its blitz against airfields and British cities in the summer of 1940. The defeat of the Luftwaffe essentially made Britain safe from invasion. And army generals, initially all older officers with Great War experience, tried to train their men for a new era of warfare. They were, said General Andrew McNaughton (successively the commander of the First Division, the Canadian Corps, and the First Canadian Army), “the cover crop” while the younger leaders learned their trade.

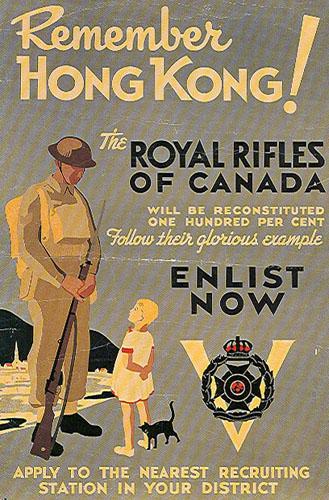

While the RCN and the RCAF had their first taste of action, the army trained and trained some more in Britain. The first combat for the Canada’s soldiers, however, came not in Europe but in Hong Kong. London asked for troops in the autumn of 1941 to bolster the Crown Colony’s defences against the Japanese. Canada duly dispatched two battalions of infantry and a brigade headquarters, which arrived in November. In short order they came under attack on December 7, and fought well, but the Japanese out-gunned them. Soon, Japanese forces overran the headquarters of Canadian commander Brigadier J.K. Lawson, who radioed that he and his staff were “going outside to fight it out.” None survived.

The Canadians surrendered by British order on Christmas Day and spent almost four years in appalling conditions in Japanese camps. The only bright spot in a dark time was that the United States was now in the war – something that would lead to victory, but the survivors of Hong Kong would not see Canada again until after August 1945.

About the author

Historian J.L. Granatstein is a member of the Macdonald-Laurier Institute’s Research Advisory Board. He taught history at the postsecondary level for 30 years. A bestselling author, Granatstein was the director and CEO of the Canadian War Museum. He writes on Canadian military history, foreign and defence policy, and politics. Among his publications are Canada’s War, The Generals, Canada’s Army, and Who Killed the Canadian Military? He is an officer in the Order of Canada.