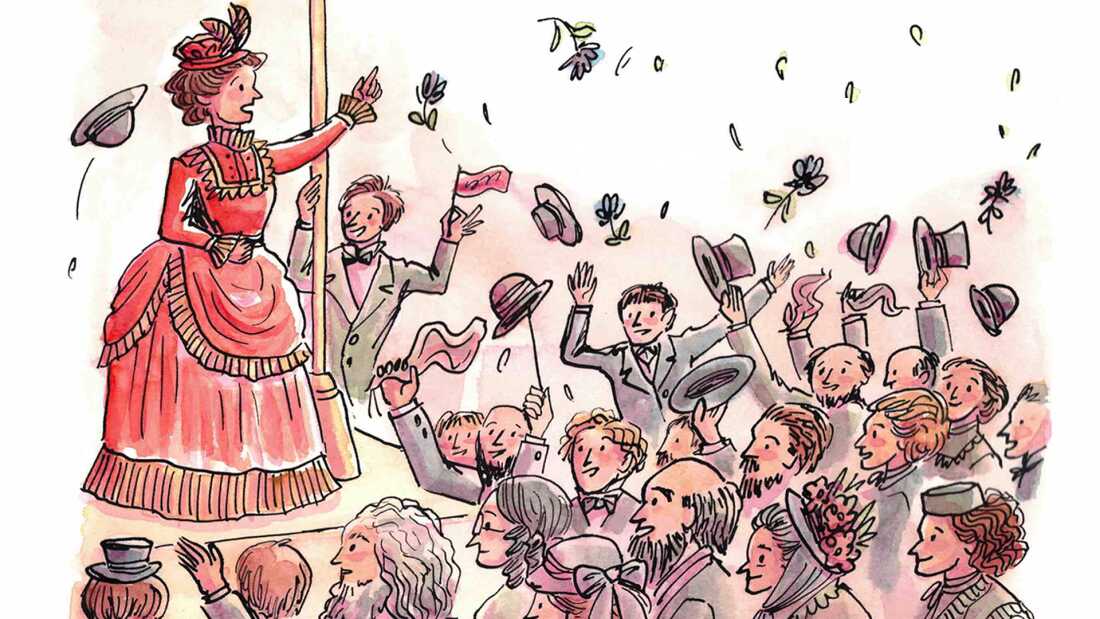

For Women’s History Month, I wanted to highlight Victoria Woodhull, who wrote a letter to the New York Herald in 1870 announcing that she was running for president. At the time, women were not allowed to vote, but there were no laws against launching a presidential campaign — perhaps because no one could have imagined that a woman ever would.

Woodhull was a passionate suffragist who has mostly been forgotten by history. The suffragists of her time kept their distance because she had other “scandalous” views they didn’t want to tarnish their cause. She was also a divorced woman with a controversial past, as a Spiritualist clairvoyant and the daughter of a conman who had roped his family into numerous criminal schemes.

However, as someone who went from uneducated bumpkin to one of the richest and most controversial people of her era, and someone who was not afraid to take action against injustices, and who went from riches back to rags in order to promote her ideas for a better nation, she ought to stand amongst the most iconic Americans in history.

Jackie Lay works on the Visuals team at NPR. She’s an animator and illustrator who has been published at The Atlantic, Vox and The Washington Post. Find more of her work online, at JackieLay.com.