The Supreme Court said Thursday that the Trump administration must “facilitate” the release of a man the government admitted it wrongly deported to El Salvador, sending the case back to the judge who ordered his return for further clarification of her order and leaving the ultimate fate of the case unclear.

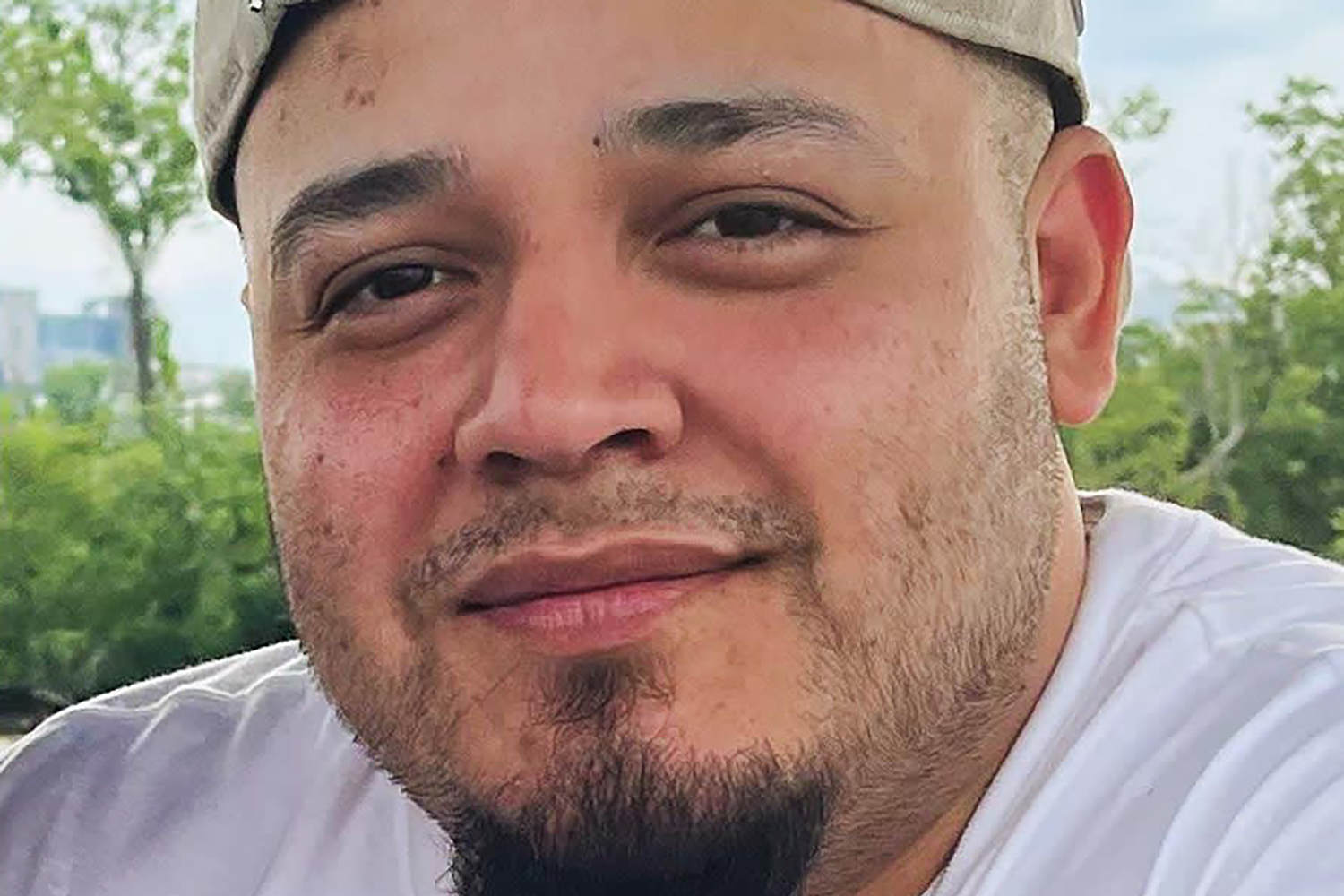

After the Trump administration admitted that it had wrongly deported Kilmar Abrego Garcia to El Salvador, a federal judge in Maryland had ordered the government to “facilitate and effectuate” his return by 11:59 p.m. Monday, April 7. A federal appellate panel declined the administration’s request to halt the judge’s order, but Chief Justice John Roberts temporarily granted the request on the afternoon of that midnight deadline, pending further word from him or the full high court.

That word came Thursday with an order that said the judge had properly required the government to “facilitate” Abrego Garcia’s release from custody in El Salvador and to ensure that his case is handled as it would have been had he not been improperly sent to El Salvador. But the order also said that the “intended scope of the term ‘effectuate’ in the District Court’s order is, however, unclear, and may exceed the District Court’s authority,” adding: “The District Court should clarify its directive, with due regard for the deference owed to the Executive Branch in the conduct of foreign affairs. For its part, the Government should be prepared to share what it can concerning the steps it has taken and the prospect of further steps.”

In statement accompanying Thursday’s order, the court’s three Democratic appointees said they would’ve declined to intervene in this litigation and effectively held the government to the judge’s directive.

“Nevertheless, I agree with the Court’s order that the proper remedy is to provide Abrego Garcia with all the process to which he would have been entitled had he not been unlawfully removed to El Salvador,” Justice Sonia Sotomayor wrote, joined by Justices Elena Kagan and Ketanji Brown Jackson. “That means the Government must comply with its obligation to provide Abrego Garcia with ‘due process of law,’ including notice and an opportunity to be heard, in any future proceedings.”

“In the proceedings on remand, the District Court should continue to ensure that the Government lives up to its obligations to follow the law,” Sotomayor added, with “remand” referring to the process of a case being sent back to a lower court.

The justices are assigned to field emergency litigation from different geographical regions across the country, and this one from the Richmond, Virginia-based 4th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals went to Roberts. When justices receive such emergency applications, they can rule themselves or refer matters to the full court for decision. Significant matters are typically decided by the full court, though the relatively short timeline on the day he issued the temporary relief could have motivated Roberts to act alone.

The court was also busy with another case that day, which became apparent later on Monday when the high court split 5-4 in a separate appeal to grant the Trump administration emergency relief in its use of the Alien Enemies Act to conduct deportations. Dissenting in that case, Sotomayor cited Abrego Garcia’s then-pending case to warn about the dangerous nature of the government’s position that it doesn’t have to return erroneously deported people. “The Government’s resistance to facilitating the return of individuals erroneously removed to CECOT [El Salvador’s Center for Terrorism Confinement] only amplifies the specter that, even if this Court someday declares the President’s [Alien Enemies Act] Proclamation unlawful, scores of individual lives may be irretrievably lost,” Sotomayor wrote.

Notably, the Supreme Court majority said in that case that people facing deportation under the Alien Enemies Act are still entitled to due process. In a filing to the justices on Tuesday, Abrego Garcia’s lawyers cited Monday’s Alien Enemies Act ruling in writing that, while his case doesn’t involve that act, the court’s due process protection in that case “supports Abrego Garcia’s position that the Government violated his due process rights by removing him to El Salvador.” They wrote that the justices’ unanimous insistence on due process “underscores that Abrego Garcia — who was removed without reasonable notice or an opportunity to challenge his removal before it occurred, and in conceded violation of a court order prohibiting his removal to that country — must have a remedy for this constitutional violation.”

In its Supreme Court application to halt U.S. District Judge Paula Xinis’ order ahead of her deadline in Abrego Garcia’s case, the government conceded making an “administrative error” in sending him to El Salvador. But it said that still doesn’t give district judges license “to seize control over foreign relations, treat the Executive Branch as a subordinate diplomat, and demand that the United States let a member of a foreign terrorist organization into America tonight.”

In the application, filed before the justices ruled in the Alien Enemies Act case, U.S. Solicitor General John Sauer said the order from Xinis, an Obama appointee, was “unprecedented” in “dictating to the United States that it must not only negotiate with a foreign country to return an enemy alien on foreign soil, but also succeed by 11:59 p.m. tonight.”

Justifying her order, Xinis wrote that the government acknowledged it “had no legal authority to arrest him, no justification to detain him, and no grounds to send him to El Salvador — let alone deliver him into one of the most dangerous prisons in the Western Hemisphere.” As to the government’s claim that he’s an MS-13 gang member, the Maryland judge wrote: “The ‘evidence’ against Abrego Garcia consisted of nothing more than his Chicago Bulls hat and hoodie, and a vague, uncorroborated allegation from a confidential informant claiming he belonged to MS-13’s ‘Western’ clique in New York — a place he has never lived.”

Opposing the government’s high court application, Abrego Garcia’s lawyers wrote that their client “has never been charged with a crime, in any country. He is not wanted by the Government of El Salvador. He sits in a foreign prison solely at the behest of the United States, as the product of a Kafka-esque mistake.”

Before winning temporary relief from Roberts, the administration failed to get the 4th Circuit to halt Xinis’ order. In separate opinions explaining their views, the appellate judges wrote that the government “has no legal authority to snatch a person who is lawfully present in the United States off the street and remove him from the country without due process,” that the government’s contrary arguments are “unconscionable” and that there’s “no question that the government screwed up here.”

Subscribe to the Deadline: Legal Newsletter for expert analysis on the top legal stories of the week, including updates from the Supreme Court and developments in the Trump administration’s legal cases.