Sports News

“You even made me look good.”

-

Bracket Championship: What’s the best trade in Boston sports history?

-

Jayson Tatum leads Celtics in business-like win over Trail Blazers: 7 takeaways

Word of artist Armand LaMontagne’s death came in the form of a phone call I received from former Sports Museum chair Dave Cowens on March 7.

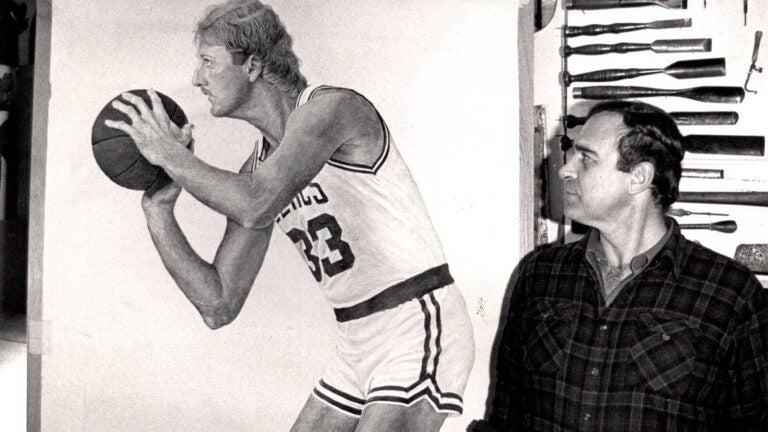

Armand was 87, but still, the news came as a shock because my image of him was that of the robust sculptor holding court in the studio of the replica 1690 Rhode Island stone-ender he’d built himself in the 1960s.

In many ways he was a man of a different century. His legacy is that of having been, in the estimation of many, America’s greatest wood portrait sculptor. He was also one hell of a carpenter and painter. The Sports Museum displays many of his best works in both artistic mediums. He is our enduring star.

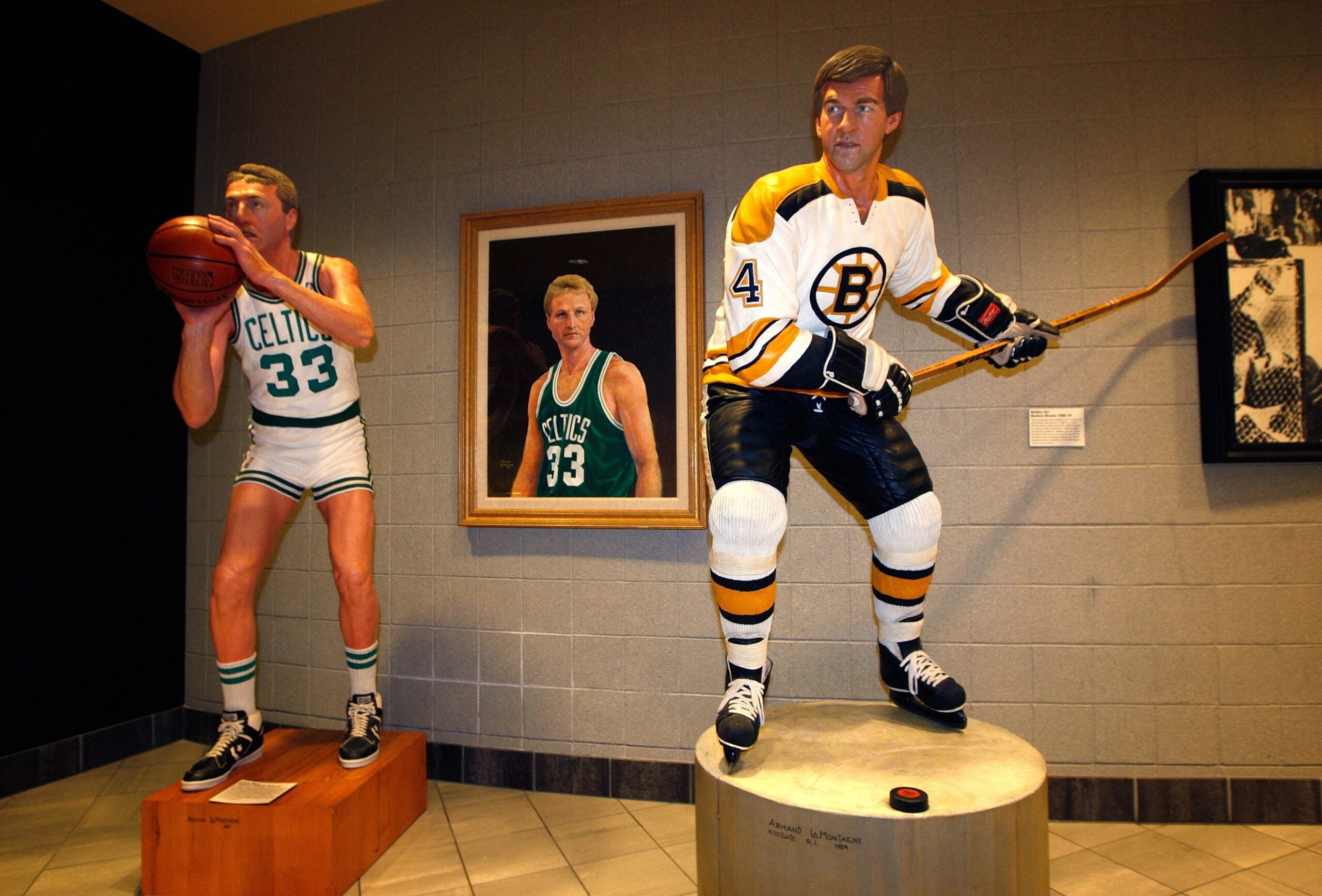

Dave and I agreed how lucky we’d been to be his friends, while enjoying his company during the period of his greatest creative output, the three decades in which he carved life-size wooden sculptures of General George S. Patton, Babe Ruth, Ted Williams (twice), Larry Bird, Bobby Orr, Carl Yastrzemski, and Harry Agganis.

We’d even reached out to Bill Russell, as we wanted to honor Boston’s greatest champion with a LaMontagne original, but he respectfully declined. I recall that Armand had even selected a pose of Russell balancing on one leg while cradling a rebound, in the split-second before he’d fire a bullet pass to Bob Cousy or Sam Jones at the start of a patented Celtics fast break.

It had been a little more than six years since I’d seen Armand, and I was aware he’d suffered a series of illnesses. Our last phone chat had been roughly a year ago, when we recalled the many times we’d interacted regarding the five sculptures and half-dozen paintings he’d created for The Sports Museum. I informed him that he was still the star of our exhibits, as visitors often stood in wonder while examining the near-Baroque swirls and almost surgically rendered intricacy of his carvings of items such as Orr’s hockey gloves or Bird’s high-top sneakers.

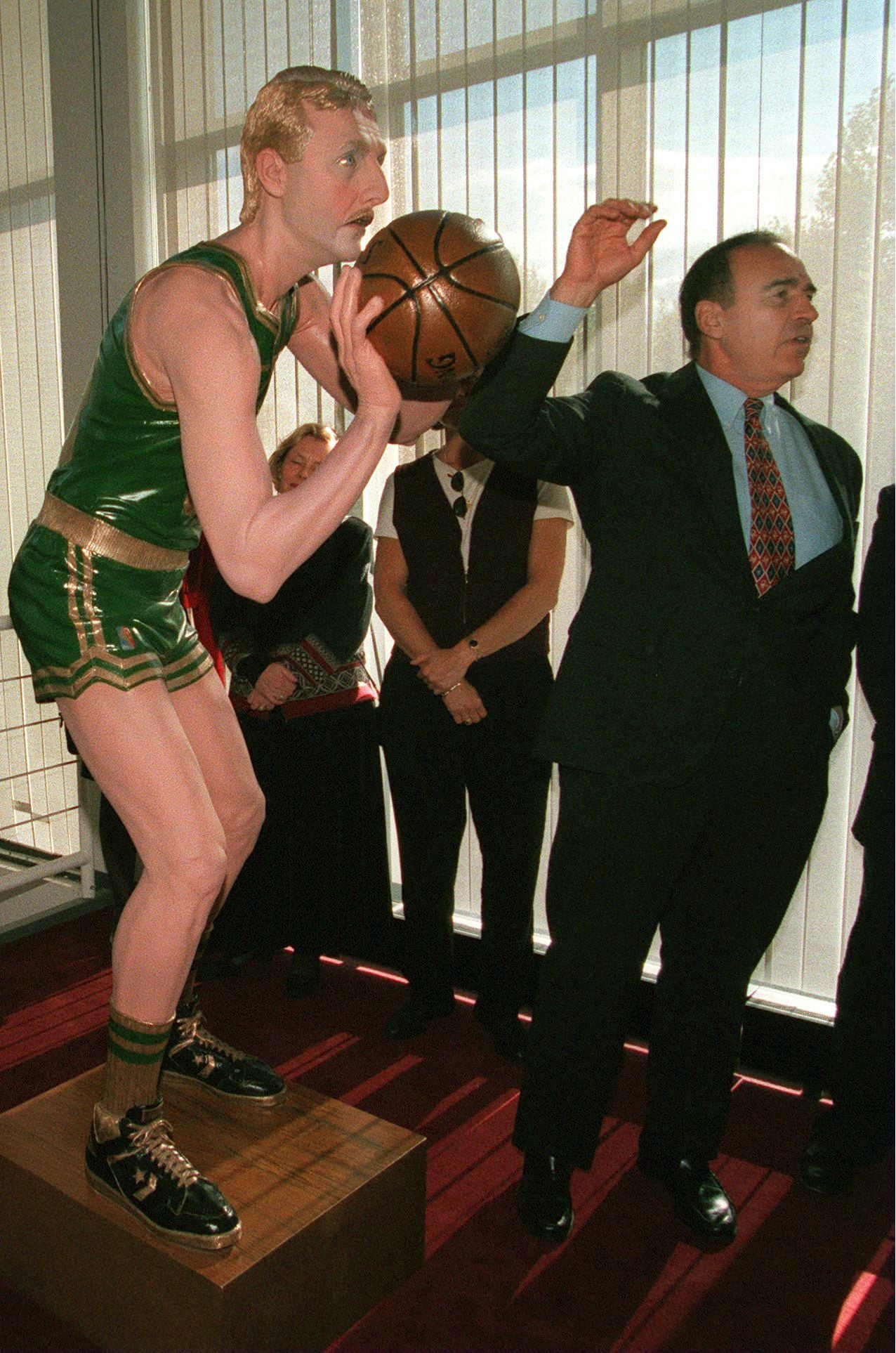

It reminded me of an encounter I had with Tom Heinsohn in the bowels of the old Boston Garden on the night of the public unveiling of the Bird sculpture. As I stood guard over the draped figure, Heinsohn approached and asked if I could give him a peek at the sculpture. After gazing at it for nearly a minute, he informed me it was just “pretty good.” Screwing up my courage, I blurted out my immediate reply of, “Just pretty good … why do you say that?”

He looked down and pointed to the sculpture’s feet and said, “Well, for starters, he put socks and shoes on a mannequin.”

Seizing on the moment, I said that though we normally wouldn’t let anyone touch the sculpture, he was, well, Tom Heinsohn, the artist and basketball star, and I told him to run his fingers over both the socks and sneakers and tell me what he thought. I may have been the first person since Red Auerbach to render him speechless, as the look on his face told me all I needed to know about his revised opinion of the artist.

In like manner, all of Armand’s living subjects came to the realization they’d dealt with a gentleman every bit as skilled, talented, and devoted to his chosen profession as they were to theirs.

As with many of the best relationships that forged the early history of The Sports Museum, our decades-long relationship with Armand started with Ted Williams before being brought home by Dave Cowens.

In the summer of 1986, I was invited to speak at the Rhode Island chapter of the Society for American Baseball Research. The invitation came from my good friend Father Gerry Beirne, who was hosting the gathering at his then-parish of St. Rita’s in Warwick, R.I. I recall it was a sunny Saturday on which I turned down an invitation to go sailing with my uncle in Portsmouth, N.H., after nearly literally flipping a coin to make my decision.

Armand was the first speaker and star attraction, because a year earlier he’d made headlines by carving a life-size wood sculpture of Williams for the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

At the Cooperstown unveiling ceremony his rendition of Williams prompted the aging slugger to break down while praising LaMontagne. Not only was an American hero honored in a picture-perfect setting, but a star was born, as news coverage of LaMontagne made national headlines.

After acknowledging a brief standing ovation in the packed reception room, he began his remarks by asking if anyone among the assembled knew anything about “a sports museum in Boston.” My hand shot up as people swerved to observe me (at this point the museum was a year from opening to the public), and Armand replied, “I want to see you afterwards.”

Ninety minutes later, after I spoke of the 1914 Miracle Braves on an afternoon where we also learned of the greatness of Bing Miller, Nap Lajoie, and Gabby Hartnett, Armand asked me to help him get something from the trunk of his vintage Mercedes.

As his trunk door lifted, he informed me that he was giving the museum a work of art at the request of Williams. We carefully cradled a long tube of rolled watercolor paper.

Back in a quiet corner of the reception hall, we unfurled what was a life-size painted study of the Williams sculpture in Cooperstown. The detail was striking, worthy of any work by Norman Rockwell or Thomas Eakins. It depicted Williams in what he considered his greatest season of 1957, the year in which he batted .388 at the age of 38, striding into a pitch with each measurement of his figure scrawled in pencil.

Williams had even signed it to Armand with the slightly self-deprecating inscription, “You even made me look good.”

Not only was it the “blueprint” for the sculpture, as Armand informed me that he clipped it to an easel adjacent to the wood block, but a masterpiece in its own right. I consider it the equal of its three-dimensional twin in Cooperstown, and proof that his artistry is as much of an engineering feat as it is an aesthetic expression.

Armand joked that at their first meeting, Williams told him he was expecting to meet an artist in a beret with a French accent. Months later, the two became close enough that when the slugger half-kiddingly complained that work on the sculpture hadn’t progressed to his liking, Armand held up his chisel and mallet and suggested that Williams finish it.

The former Army vet and Marine fighter pilot became fast friends, and The Sports Museum proudly displays one sculpture of the slugger in his fly-fishing gear to accompany the four Williams painted portraits that are among our treasures.

Not long after he’d presented the museum with the study for the Cooperstown sculpture, he asked if we could connect him with Bird in the hope the Celtics star would agree to pose for a sculpture. Cowens reached out to his former teammate that night, and within 48 hours Bird and Cowens drove Larry’s pickup down to the artist’s studio, where No. 33 agreed to pose.

Ten months later, that sculpture was unveiled first at a private dinner at the Ritz-Carlton Hotel and later prior to a game at Boston Garden. At the Ritz dinner, Bird made brief remarks that included casting a glance to Orr before informing the group he always looked at Orr’s retired number banner during the playing of the national anthem to gain inspiration.

That Hollywood moment led to Armand’s next commission, namely an Orr sculpture, followed two years later by Yastrzemski, the classically rendered Agganis in 1995, and finally the Williams fishing sculpture in 2001.

Each have their distinctive characteristics, with Orr captured in a dazzling array of carved and painted details, the torque and grace of Yastrzemski’s swing (the subject commenting to LaMontagne that he captured him socking a home run), the classic pose of Agganis (that one critic observed resembled Zeus tossing a thunderbolt from the heavens), and Williams shown in his happy place of the salmon streams of New Brunswick. The ailing slugger saw it weeks before his death in 2002, and declared it his favorite portrait of himself.

Like his noted subjects, LaMontagne will be remembered as one of the greats. In the context of art history, that leads to an immediate comparison with Grinling Gibbons, England’s master wood sculptor of the late 17th and early 18th centuries whose most noted works reside within London’s St. Paul’s Cathedral. I recall surprising Armand by comparing him to his artistic counterpart, which made him laugh before replying with a robust, “That’s my guy.”

Armand, was, and will forever be, our guy.

Richard Johnson has served as curator of The Sports Museum since 1982.

Get the latest Boston sports news

Receive updates on your favorite Boston teams, straight from our newsroom to your inbox.