After killing 26 tourists in Baisaran, a meadow near Pahalgam in the lap of the Pir Panjal mountains, the five terrorists are learnt to have fled to the surrounding jungles that are spread across hundreds of kilometres of rugged, difficult terrain.

This has left security forces with a daunting challenge — one that underlines the importance of a robust anti-infiltration grid to prevent terrorists from crossing over in the first place.

India and Pakistan share a more than 3,300-km-long border, of which close to 1,000 km lies in Jammu & Kashmir.

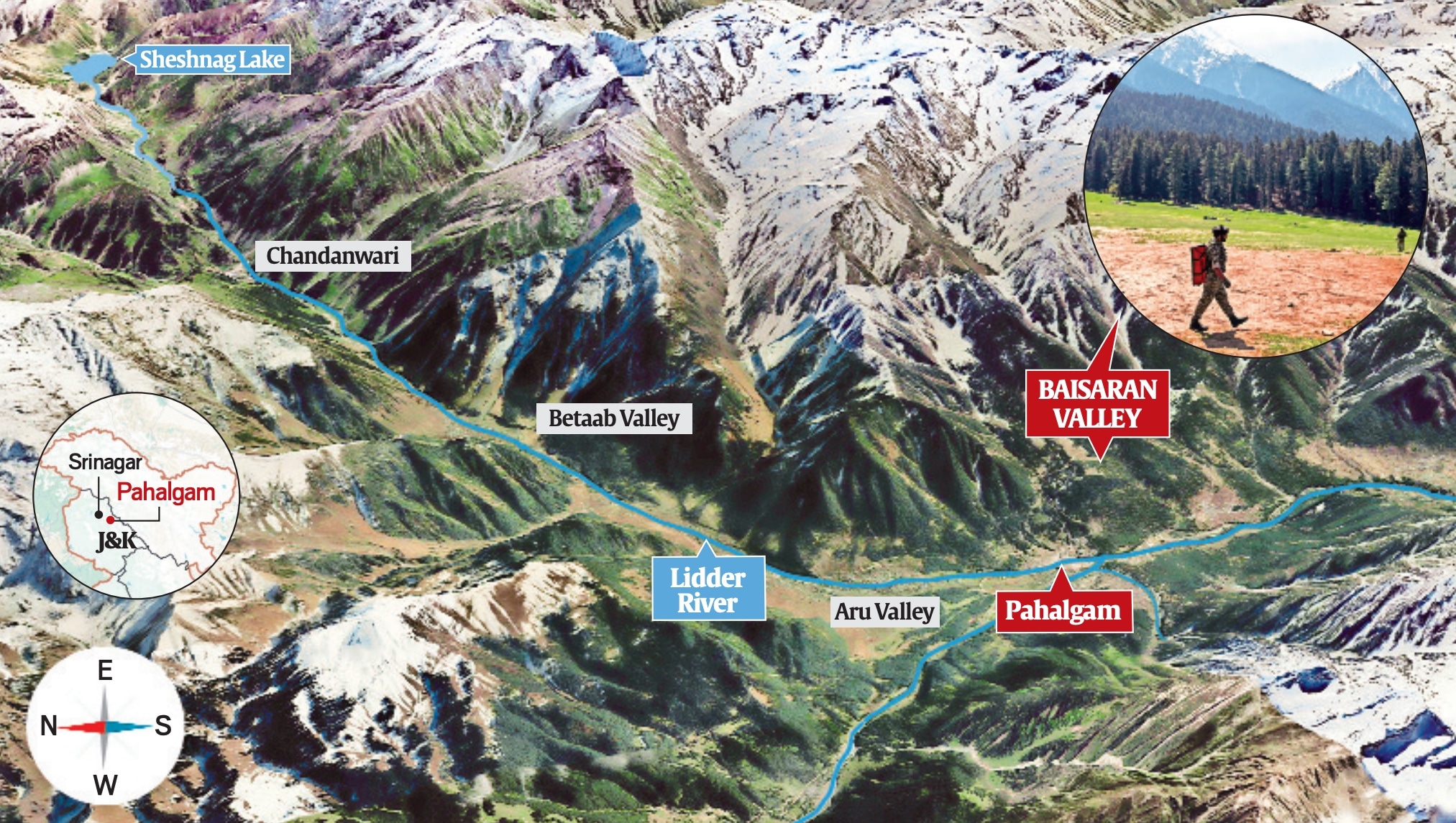

Baisaran, 6 km from Pahalgam, is accessible only on foot or by pony. The meadow is ringed by the densely forested Pir Panjal mountains that stretch far, toward Kokernag and Kishtwar to the south and Balatal and Sonamarg to the north. (Express graphic, Google Maps)

Baisaran, 6 km from Pahalgam, is accessible only on foot or by pony. The meadow is ringed by the densely forested Pir Panjal mountains that stretch far, toward Kokernag and Kishtwar to the south and Balatal and Sonamarg to the north. (Express graphic, Google Maps)

Challenge of the hunt

The dense jungles in the upper reaches of the Pir Panjal range provide ample avenues to avoid detection. Sources say visibility in these jungles is so poor that it is difficult to spot movement even 100 metres away. Tracking down suspects in these parts requires robust technical and human intelligence support.

Over the last few years, the armed forces have suffered serious casualties chasing terrorists in these jungles — more than 50 Army personnel have lost their lives in encounters with terrorists in the Poonch, Rajouri, Kathua, and Doda regions.

This is perhaps a direct consequence of Pakistan sending in highly trained terrorists, who operate in stealth and live off the jungle, into the Jammu region. Their lack of contact with locals, and use of advanced, stealthy communication devices has made it difficult to hunt them down.

Sources say the Pahalgam terrorists were likely of this kind. At least three of the attackers are suspected to be from Pakistan.

Story continues below this ad

Stopping infiltration

“Once a terrorist is in, it is not easy to hunt him down… So the idea should be to not let him enter in the first place,” a senior security establishment officer told The Indian Express.

This is why a robust counter-infiltration grid, which includes difficult-to-breach fencing, a strong intelligence network, and trained border-guarding manpower, is the need of the hour. This is more so because terror recruitment in the Valley itself is the lowest it has ever been. Chief of Army Staff General Upendra Dwivedi in January said that 60% of the 73 terrorists killed in counter-terror operations in J&K in 2024 were from Pakistan.

Data support the effectiveness of border fencing, which picked up pace after the 2003 ceasefire agreement between India and Pakistan. According to Intelligence Bureau figures, more than half of all infiltration attempts were successful in 2002. By 2010, only a fifth of the attempts (52 out of 247) met with success.

“In the ’90s, the infiltration would be in the thousands [a year]… Now it has tapered off to between 50 and 100,” a J&K Police officer said.

Story continues below this ad

Status of the fence

The India-Pakistan border (including the Line of Control) is almost entirely fenced. Since 2014, there has been a push to make this fencing more robust, and plug riverine gaps in the Jammu region with technological solutions.

This received a major impetus with the Comprehensive Integrated Border Management System (CIBMS) project, launched after the 2016 Pathankot attack. The CIBMS deploys a range of state-of-the-art surveillance technologies — thermal imagers, infra-red and laser-based intruder alarms, aerostats for aerial surveillance, unattended ground sensors, radars, sonar systems for riverine borders, and fibre-optic sensors — that provide real-time surveillance data to a command and control system.

However, it remains a work in progress. In October 2016, then Union Home Minister Rajnath Singh had announced that the India-Pakistan border would be sealed by December 2018. Cut to December 2023, with work still pending, Home Minister Amit Shah revised the deadline to December 2025.

Progress of the CIBMS has been slowed by the non-availability of required technology and, at times, incoherent planning. Some of the suggestions floated in MHA meetings following the Pathankot attacks bordered on the bizarre.

Story continues below this ad

For instance, to plug the vulnerability at riverine patches, one suggestion was to install motorised pulleys that would constantly ferry a patrolman back and forth. This was (wisely) shot down on the grounds that if the motor malfunctioned, the sentry would be left literally hanging, a sitting duck.

Weather and other challenges

Apart from plugging riverine patches, fencing and border security along the LoC presents numerous challenges. During winter, the LoC experiences heavy snowfall: snow can pile up to 15 feet high. Almost a third of the border fence gets damaged annually as a result.

“Pickets get bent and the concertina is crushed, which takes three to four months to fully repair. All the material has to be hauled up through tough terrain, making repairs an enormous task,” said Lt Gen D S Hooda (Retd), former General Officer Commanding-in-Chief of the Indian Army’s Northern Command. He added: “The time this process takes [to fix fences] leaves gaps which are exploited by terrorists.”

At the end of the day, however, terrorists are known to cut through even erect three-layer fences. This means infiltration can only be stopped by alert personnel who respond to breaches.

Story continues below this ad

“A lot of manpower is stationed along the LoC. But these are inhospitable conditions with winter temperatures going way below freezing. Fog and rain can impact alertness. Sometimes, we used to struggle to give one full night’s sleep to a soldier in three days,” Hooda, who retired in 2016, said.

Technology, too, has its limitations. “Gadgets such as night-vision devices have a particular life. They don’t last for 12 hours. And at many places, there is no power to charge them,” he said.

Need technology, investment

Sources said the government must build fences that can withstand heavy snow. Technology to detect tunnels and human movement in adverse weather conditions, and significant aerial surveillance support, must be deployed in all vulnerable areas, they said.

“What we need is a smart fence. One design we are looking at includes a sensor which sends a message to the nearest command centre the moment the fence is cut. There is a cost associated with all this. But it is worth it,” Hooda said.