By Nigel S.B. Rawson and John Adams

March 13, 2025

Introduction

Health care across Canada is in crisis. In addition to known burdens of disease and therapies, Canada’s processes have become too bureaucratic and burdensome. With more barriers and layers of gatekeepers than any other country, Canadians are being forced to wait unacceptably long to access new and potentially lifesaving therapies.

There’s already significant shortages of doctors, nurses and hospital beds, several million Canadians have no family physician (Duong and Vogel 2023), emergency rooms are overrun with people who have nowhere else to turn for medical treatment (Kirkey 2024; Zafar 2024), and wait times to see a specialist and for surgery are far too long (Moir and Barua 2023) such that patients can die before seeing a health care provider.

Reasons include too many gatekeepers (well-paid administrators and politicians) poorly managing the “system” with perverse incentives, counterproductive billing codes, and insufficient health professionals where the rubber hits the road (Corbella 2022). An excessive number of gatekeepers negatively impacts the drug approval and pricing processes.

We are in a golden age of biotechnology and medicine. However, a key problem is our policies and practices get in the way. Increasingly, a drug prescribed by a physician who knows the patient and their condition is viewed by the insurance payer (public or private) as a suggestion to be second-guessed by prior authorizations and payment criteria, not a medical necessity. Medicines only work if patients can access and use them. Delays in access mean patients’ health and quality of life deteriorate and lives are lost prematurely. The time between a medicine’s development and patients’ ability to use it is a key metric. Four years can often elapse between the first government in the world paying for a new drug and when the first Canadian can get that drug via a government drug plan (CHPI 2024). This is deliberate rationing of access to treatment, which can be lethal to patients with aggressive conditions.

Properly prescribed and used, innovative medicines can cure or alleviate disease, slow, halt, or reverse the course of illnesses, and extend lives, providing a better quality of life and preventing the need for other more expensive medical services (Bobrovitz et al. 2018). However, instead of encouraging drug developers to launch these medicines in Canada, federal, provincial, and territorial governments have established gatekeeping processes using flawed evaluations of the benefits and costs of new drugs and controlling their prices. It is getting worse as more private payors wittingly or unwittingly borrow bad practices from governments and apply recommendations never intended to consider what is best to keep people healthy, working, and, as a result, paying taxes (Bailey 2024; Lepage 2024; Lepage and Eagan 2024). This situation plays a significant role in Canada’s lack of productivity

These flawed processes, in aggregate, can deter drug developers from bringing novel medicines to Canada (Rawson 2022). New medicines may be costly for drug budgets but can save money by preventing the need for more and more expensive health care services and maintaining worker productivity. Canada’s siloed health care gatekeepers and their masters fail to take a whole-of-society or even a whole-of-healthcare view for evaluating benefits of new medicines (Lau et al. 2024).

It’s important to understand how new medicines are approved and reviewed for coverage in government drug plans. There are five gatekeeping layers to get drugs to Canadians through government systems:

- Submission to Health Canada for regulatory review before marketing a drug.

- Submission for health technology assessment (HTA) by the institute national d’excellence en santé et services sociaux (INESSS) for the Quebec’s drug plans and Canada’s Drug Agency (CDA) for government drug plans in the rest of Canada.

- Negotiations between drug developers and the pan-Canadian Pharmaceutical Alliance (pCPA), the federal, provincial, and territorial governments’ price-negotiating organization.

- Negotiations between drug developers and individual government drug plans.

- Assessment of whether a drug’s Canadian price is excessive compared with prices in a set of other countries by the federal tribunal called the Patented Medicine Prices Review Board’s (PMPRB).

No other country has so many layers of gatekeeping for biopharmaceutical health care.

Gatekeeper 1: Regulatory review by Health Canada

The first step towards launching a new medicine in Canada is to submit data about its benefit, safety, and manufacturing quality to Health Canada for approval to market the drug. If Health Canada grants priority status for a first-in-class drug for an unmet need, this step takes about six months. Otherwise, such evaluations take around a year (Rawson 2018).

New medicines are submitted to Health Canada typically about a year after submission to either the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) or the European Medicines Agency (EMA), both of which are larger and better funded regulatory agencies than Canada’s. Both the FDA and EMA already analyze data submitted by drug developers, while Health Canada seems to repeat those reviews.

This initial delay could be due to several reasons, but two are particularly relevant. First, Canada’s population of 40 million is small when compared with the US population of over 330 million and the European Union’s almost 450 million. The other reason is barriers erected by Canadian governments that drug developers must overcome to get their medicines to Canadians.

Gatekeeper 2: Health technology assessment by Canada’s Drug Agency

The roots of Canada’s Drug Agency (CDA) extend back to 1989. It expanded in 2006 and became the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health. In 2024, the agency rebranded itself as CDA. Today, it is a large non-profit corporation with over 250 staff and a budget of $50 million in 2022–23 (latest statement available), with 83 per cent of its revenue coming from federal (81.5 per cent) and provincial (18.5 per cent) governments (KPMG 2023). Why federal taxpayers pay more than 80 per cent is worth asking, when CDA mostly serves provincial and territorial responsibilities for health care. This could be an item crying out for a cutback to help trim the federal deficit while respecting the primary responsibilities of provinces and territories for health care. They should pay more if they value its performance.

CDA does the work of and for governments but, despite its name, is not a government agency, which means freedom-of-information requests, independent ombudsperson appeals, and auditor-general performance reviews, let alone regular parliamentary scrutiny, are not available to examine its independence, transparency, or accountability (Rawson and Adams 2017).

The key role of CDA is to perform HTA reviews to try to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of new medicines and make recommendations about reimbursement to all government drug plans, except those in Quebec. HTA is a methodology – not a science (Hofmann 2013) – and, unfortunately, CDA HTAs are flawed in major ways. We count eight distinct defects in the function and performance of CDA.

The first flaw is that its evaluations are based on inadequate data because effectiveness is unavailable from premarketing clinical trials. Randomized clinical trials measure efficacy, which is the extent to which an intervention “produces a beneficial result under ideal conditions,” whereas effectiveness is the extent to which an intervention “when deployed in the field in routine circumstances, does what it is intended to do for a specified population” (Rawson 2001). HTAs are, therefore, predicting a drug’s benefit in regular clinical practice based on evidence from the experimental environment of premarketing clinical trials where patients carefully selected to have a precise diagnosis are vigilantly monitored to ensure the medicine is administered at the right dose at the correct time. In the real world, patients may not have the same diagnosis, not use the drug as directed, and aren’t supervised to the same extent.

A second limitation is the price used in CDA HTAs. Usually, it’s the drug’s list price, which is higher than the price negotiated by large purchasers, such as government drug plans. Consequently, no matter how sophisticated CDA analyses appear to be, they use inaccurate data to make predictions that affect whether patients should receive coverage by government drug plans.

A third questionable practice is that CDA HTAs are duplicating work done by Health Canada, which is especially concerning when CDA not only replicates the regulatory agency’s work but second-guesses Health Canada by questioning a drug’s clinical benefit.

The fourth area for error is about assumptions. Like most HTA agencies, CDA prefers cost-utility economic analyses, which use a metric known as quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) that attempts to include both quality and quantity of life lived in a single measure of disease burden. QALYs use a linear scale between zero representing death and one representing perfect health and are, therefore, a one-dimensional measure of an individual’s quality of health that, in reality, is a complex, multi-faceted and non-linear physical, psychological, and social state (Pettitt et al. 2016; Prieto and Sacristán 2003). The linear scale of QALYs is arbitrary and inconsistent with the real world and patient impact.

HTAs are based on modelling techniques requiring numerous assumptions. The use of QALYs adds a further layer of suppositions. Although experts have developed sophisticated methods to try to overcome these issues, they can never overcome problems caused by unrealistic or illogical assumptions and inadequate or inaccurate data. QALYs also fail to capture the social value of a medicine (Rowen et al. 2017) and are a deficient and inequitable measure of health quality for assessing the value of treatments for people with disabilities, chronic conditions, or rare disorders (National Council on Disability 2019; Richter et al. 2018).

A fifth flaw is the assumed value of a QALY. CDA compares QALYs with a willingness-to-pay threshold value to assess a “cost-effectiveness ratio.” In the past, the threshold for a QALY wasn’t explicitly stated, although commonly thought to be $50,000 but, in some cases such as drugs for cancer or rare disorders, it was $100,000 to $150,000 (Binder et al. 2022; Fashami et al. 2024). However, in the last five years, CDA has regularly used a willingness-to-pay threshold of $50,000 per QALY to assess cost-effectiveness, regardless of the type of medicine. The $50,000 threshold was first proposed in 1990 (Grosse 2008) and never adjusted for inflation, economic growth, severity or rarity of disease or the significant increase in research, production, and regulatory costs of innovative medicines in the last four decades.

The $50,000 threshold doesn’t work well for modern medicines, given increases in longevity and population health, and, consequently, HTA reports frequently include recommendations for price reductions of 70 per cent or higher to achieve $50,000 per QALY (Rawson 2021; Balijepalli et al. 2024). Calling for 99 per cent reductions is not unheard of, but the reality is CDA’s use of a $50,000 per QALY threshold dating from 1990 means its gatekeeping is not fit for purpose. Other approaches, such as the Standard of Living Valuation that considers the value of socioeconomic conditions in addition to health benefits (Pyenson et al. 2024), should be considered to replace current methodology.

The sixth area of concern is the tunnel vision of focusing predominantly on one type of evidence. The CDA version of HTA prioritizes evidence from pivotal trials – randomized, placebo-controlled, phase 3 clinical trials – in its HTAs; earlier trials and other study types are given less weight. Randomized phase 3 trials are not always possible for rare disorders or can be unethical if an earlier study demonstrates a drug has a beneficial impact on life-threatening or debilitating diseases. CDA has a documented pattern of less flexibility than HTA agencies in other countries when considering early trials, other types of studies, and real-world evidence.

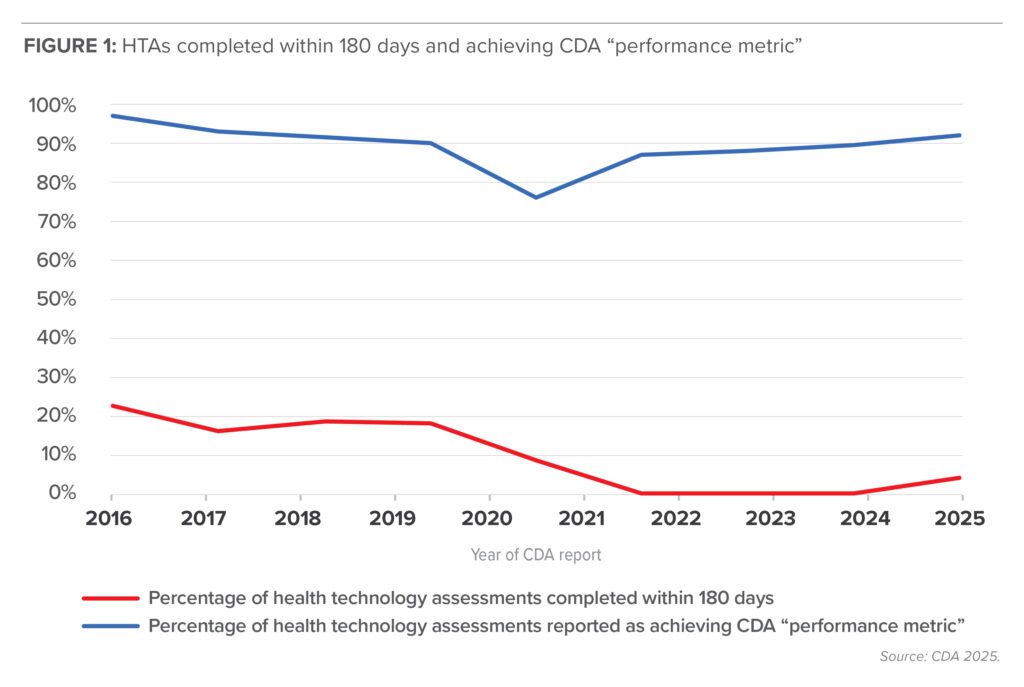

Flaw seven is that, for any patient waiting desperately for a drug available outside Canada, HTAs take precious time to complete, despite CDA’s procedures manual stating its “typical timeline” for reviews is “≤180 calendar days” (CDA 2024). Few reviews achieve this performance metric (just 52 or 9.2 per cent out of 567 published in the past nine years with mention of the metric) and the percentage has decreased over the period, but most HTA reports state CDA achieved its “performance metric” (Figure 1). The CDA version of HTA reporting is self-serving. CDA reports don’t state what the metric is, but we assume it’s 180 days. The percentages shown in Figure 1 are consistent for both oncology and non-oncology medicines (Rawson and Stewart 2024). CDA regularly fails to meet its own standard for timely reports.

CDA claims that it achieves its performance metric for all reviews, but 60 of the 567 reviews (10.6 per cent) report the metric as “N/A,” which we assume means not applicable. Over 88 per cent of the 60 reports had a comment about the delay but no details of its length. Nearly 90 per cent of the reports stating the metric was achieved had reviews extending beyond 180 days, but only 26.8 per cent had comments about the delay and, again, no details. CDA claims of timely reports are not supported by what it chooses to make public.

The eighth concern about CDA is how much emphasis is placed on the input from patients and clinicians when making recommendations. CDA requests written input from these groups as part of its HTA process. Deadlines for submissions are often tight, and busy health care providers and small under-resourced patient groups may find it difficult to comply with them, resulting in their voices not being heard adequately. Moreover, it’s difficult to ascertain from CDA reimbursement reports what weight is given to their input. Patient group submissions are considered by many to be largely tokenism. Only CDA’s oncology drug review expert committee includes patient representatives (three of its 17 members); the non-oncology drug review expert committee has no patient representatives, just three representatives of the public.

Unlike the transparency of some HTA agencies in other countries, CDA committees hold closed-door meetings and, consequently, members’ perspectives and official votes are unknown, which means that, despite numerous and extensive reports being produced by CDA about HTA reviews, the public, patients, and health care providers know little about the “black box” decision process and what evidence was given the most weight. Patients and health care professionals are often frustrated and concerned when their physicians support access to an innovative medicine in submissions to CDA, but CDA recommends not reimbursing the drug or restricting access, based on advice from its own anonymous clinicians or staff (Darke 2023; Patient Voice 2023; Tam et al. 2022).

It is not CDA’s role to set prices. Nevertheless, including price reduction recommendations in its reports allows CDA to set up a negotiating position for the pCPA if it chooses to negotiate with the manufacturer.

Gatekeeper 3: Price negotiation with the pan-Canadian pharmaceutical alliance

Like CDA, the pCPA is also owned, managed, and funded by the federal, provincial, and territorial governments, and it’s to these governments that it is accountable, not to patients and health care providers. This arrangement doesn’t satisfy a reasonable interpretation of the good governance principles of independence, transparency, and accountability (Rawson and Adams 2017).

The pCPA has up to 40 business days to decide whether to negotiate once a reimbursement recommendation is published (pCPA 2023), but the target timeline is regularly not achieved. For medicines with a CDA recommendation in the last nine years, the time to decide whether to negotiate was within 40 days for only 26.3 per cent. Since it’s the pCPA’s decision whether to negotiate, delays in doing so are entirely its responsibility. The pCPA also has a performance target for negotiations of 90 business days (pCPA 2023), and again this is often exceeded. For medicines with a CDA recommendation in the last nine years, the negotiation time was within 90 days for 42.5 per cent; so far for medicines with CDA reports issued in 2024, it’s 96.6 per cent (Figure 2), but this figure is based on only 29 of 68 CDA reviews issued in 2024 with a positive recommendation. Consequently, it takes, on average, over a year between submission to CDA and a pCPA outcome (CHPI 2024).

Gatekeeper 4: Listing by Government drug plans

Even when a medicine has a CDA positive recommendation and a successful pCPA negotiation, patients can’t get access via a government drug plan until plan officials have added the drug to the benefit list. Government drug plans are not mandated to list medicines that successfully pass through the Health Canada, HTA, and price negotiation steps. They can negotiate further price and other concessions with the developer before deciding whether or not to list a drug. On average, it takes about six months from a successful pCPA negotiation to the first listing in a provincial drug plan (CHPI 2024). All the process delays add up. Patients can literally wait forever before the final province lists a drug.

Drug plan officials have no motivation to list a medicine due to perverse incentives. The siloed nature of government accounting means any proposed increase in the drug plan budget is not balanced against potential savings from fewer emergencies, hospitalizations, or specialist services, or an early return to work, school, or family to take a broader economy or societal perspective. The time taken by gatekeepers to decide whether to list a new drug further extends the delay for patients waiting to get access to it. The result is that listing of drugs varies substantially across Canada. Critics call this the “postal code lottery” for access to a new medicine.

Listing doesn’t necessarily mean patients have financial coverage of a drug. Provincial drug plans have varying requirements for coverage. They all cover seniors, social assistance recipients, and children. Other special groups, such as people with diabetes, may also be covered. However, how patients receive coverage also varies. Virtually all plans require a copayment, with some having a maximum copayment amount. Some require an annual premium and at least six provinces have a deductible amount that must be paid before the plan will offer any benefit. Even then, there is variation. For example, the deductible for seniors in Ontario is $100 per year after which they only pay a dispensing fee for drugs on the benefit list, whereas in Saskatchewan, the deductible is close to $1,000 semi-annually after which the province pays 65 per cent of the costs of drugs on its much shorter benefit list, which means seniors pay for all their medicines unless they have a particularly low income or catastrophic drug costs.

Furthermore, access criteria recommended by HTA agencies and implemented by government drug plans have become more detailed and more stringent in recent years. Some criteria limit access only to children, cutting off their access after a certain age. Other criteria deny access to patients in the first stages of a disorder who might benefit most and only provide access to patients at a much later stage in disease progression when patients are much sicker and may not benefit as much. This is one of the reasons why we regard the status quo as a sickness care system, rather than a wellness system.

Gatekeeper 5: Patented Medicine Prices Review Board

The PMPRB is a tribunal established by a federal act whose role is to prevent time-limited, patent monopolies granted for new medicines from being abused by excessive prices. Its role is not to set drug prices nor to decide whether prices are reasonable or appropriate but to use a referenced-based pricing analysis to compare list prices in Canada with a set of other countries. The PMPRB is unique in the world as no other country has such a gatekeeper.

The PMPRB’s jurisdiction officially begins after a new patented medicine is sold for the first time in Canada, which means its work can start soon after Health Canada’s regulatory approval or much later after HTA and price negotiation processes have been completed. Developers have to assess whether their list price will be PMPRB-compliant and, if not, must decide whether to decrease the price to achieve compliance, keep the price and risk PMPRB action against them, let its patent lapse to avoid PMPRB jurisdiction, delay launching in Canada, or not launch here. Delaying launching means a further wait for patients; not launching denies access entirely.

The PMPRB has performed its role since 1987 using seven countries (France, Germany, Italy, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the United States) in its price comparison. Between 2017 and 2022, the PMPRB tried to expand its powers to severely reduce list prices of new drugs in Canada. The plan included replacing higher price countries (United States and Switzerland) in the comparison test with six lower price countries (Australia, Belgium, Japan, the Netherlands, Norway, and Spain), implementing new unproven pharmacoeconomic tests to determine prices, and requiring drug developers to report details of confidential rebates negotiated with public and private insurers.

The PMPRB’s plan met much opposition from patients, drug developers and others. Challenges in federal and Quebec courts led to rulings against using pharmacoeconomic tests and reporting confidential discounts as unconstitutional and violating trade secrets. The courts found that the PMPRB is “not empowered to control or lower prices” without evidence of excessive pricing (Rawson and Adams 2021). The change in countries in the price comparison test is all that remains. Some critics claimed that the federal Minister of Health capitulated to the biopharmaceutical industry by withdrawing the other proposed changes (Rawson and Adams 2023). In reality, the courts and the rule of law prevailed over an out-of-control PMPRB bureaucracy seeking power outside federal law aided and abetted by academic, civil servant, journalistic, and partisan spins.

The PMPRB is now under new governance and management (Health Canada 2023) and re-developing its role. It released new draft guidelines for consultation in December 2024 (Government of Canada 2024), although there seems to be relatively little difference between what the PMPRB has done for nearly four decades and the revised process, other than using different countries in the reference-based price comparison (Rawson and Adams 2025).

Other countries don’t have an equivalent of the PMPRB but have better access for patients and lower net prices because of negotiations. It is time to admit Canada’s unique approach to drug price regulation is an outlier, has failed, and has become mostly irrelevant. The federal government is overdue to improve the Patent Act to make the Canadian market fully competitive with other developed countries.

Solution: A New Direction

In this milieu – we can’t call the gatekeeping labyrinth a “system” – the federal Liberal government pressured by the NDP is working to introduce a national pharmacare scheme, which it claims will improve access to new medicines. We believe the federal government – especially if it’s a new one focused on balancing budgets – should take a different approach. Here are our recommendations, starting with the call for Ottawa to show greater respect for the jurisdictions of the provinces and territories that provide most of health care:

- Health Canada: The number of officials working on approving medicines for use in Canada could be significantly reduced if, instead of Health Canada re-assessing data already evaluated in more detail by the FDA and/or the EMA, recognize rigorous approvals by the FDA and/or the EMA, or other trusted regulators in the United Kingdom, Switzerland, Australia, and Japan as being sufficient for approval in Canada. Health Canada could retain a small staff for the few medicines (less than 10 per cent) that are only or first approved in this country. This would significantly shorten approval times from months to days and decrease costs significantly because only a small team would be needed to evaluate the relatively few drugs that are only approved in Canada.

- CDA: Federal funding to CDA should be drastically reduced. The vast majority (over 80 per cent) of CDA’s funding comes from the federal government. Just by reducing the federal contribution by two-thirds would save $20 million. If provinces believe that CDA’s work is vital, they should provide the money. INESSS receives no federal money. The federal contribution should be based on the one million Canadians (1/40th of the total population) covered by Indigenous Services Canada.

In addition, CDA should be required to complete at least 90 per cent of its reviews within a calendar period of 180 days between receipt of a submission and CDA’s final recommendation in line with its stated “typical timeline,” and to refund drug developer submission fees when the 180-day target is missed.

- pCPA: Health Canada also provides much of the budget for the pCPA, the collective bargaining agency. If the provinces and territories value its work, they can pay for most of it as part of their responsibilities for health care. The federal contribution should be based on those Canadians covered by federal drug programs.

All drugs with a CDA recommendation for reimbursement should, unless their developers object, be taken up by the pCPA for price negotiation when the recommendation is issued. Delays of many months before the pCPA invites drug developers to negotiate are unacceptable.

- Government drug plans: Ontario Premier Doug Ford has said: “We owe it to Canadians to do everything we can to give them the same timely access to life-changing treatments as patients in the rest of the world” (Rushowy 2024). Instead of just talking the talk, Ford needs to walk the walk and persuade his fellow premiers to do the same (Rawson and Adams 2024). The provinces effectively own and control CDA and the pCPA and each province or territory is responsible for the time it takes to list a new drug on its own plans.

Government drug plans should be required to list and fund all drugs with a positive recommendation from CDA and a successful negotiation with the pCPA within three months of the pCPA outcome. Delays by drug plans of months or years deny patients’ access and, in some circumstances, endanger their health when a treatment is available. This is an unacceptable situation.

- PMPRB: The PMPRB’s federal funding can be reduced, given its legal mandate, or the whole tribunal be disbanded. Its drug data analysis function should be transferred to the Canadian Institute for Health Information to help overcome siloed thinking about only drugs. Disbanding the PMPRB would save around $18 million per year (Rawson and Adams 2025).

- National pharmacare should be left to the provinces and territories. The provinces and territories helped build CDA and the pCPA. Provinces and territories already have their own versions of pharmacare. Like interprovincial trade barriers, all it takes is the political will to harmonize those rules and practices among the provinces and territories, if they want to. Introducing another layer to provide access to low-income Canadians is unnecessary. Removing the current cost barriers (premiums, copayments and deductibles) each government drug plan has for these Canadians would solve most of the problem without eliminating or undermining the private insurance plans two-thirds of Canadians have or creating another new national system developed by the federal government. In addition, provinces and territories can do more to help admit people who are eligible for their existing plans but not enrolled.

Conclusion

Canadians need a major renovation of the processes for new drug access. The emphasis should be on putting patients first by taking inspiration from drug insurance in places like Germany, France, and Italy where a patient can get a drug paid for by insurance, in many cases, as soon as the regulator says it has a good safety profile, has a proven clinical benefit, and a quality manufacturing process – without having to wait for HTAs and price negotiations between payers and drug developers. That would be putting patients first. Payments get adjusted later without impacting the patient. Canadians need more efficient and less time-consuming gatekeeping that enables them to receive insured access to innovative medicines as early as possible, while ongoing data collection and analysis evaluates their longer-term benefits.

A paradigm shift in thinking is particularly important for the coming generations of high cost, high benefit drugs, including cell and gene therapies. The status quo in Canada for drug access is unhealthy.

About the authors

Dr. Nigel Rawson is a pharmacoepidemiologist and pharmaceutical policy researcher. He is also an affiliate scholar with the Canadian Health Policy Institute and a senior fellow with the Macdonald-Laurier Institute as well as the Fraser Institute.

John Adams is a seasoned management consultant with a current focus on advocacy for unmet patient health needs. He has extensive experience in public policy, governance and senior management. A frequent author and commentator on health-related public issues, he is a senior fellow at the Macdonald- Laurier Institute.

References

Bailey, Lauren. 2024. “More private payers seeking to reduce costs turning to preferred pharmacy networks: expert.” Benefits Canada, May 1, 2024. Available at

Balijepalli, Chakrapani, Lakshmi Gullapalli, Juhi Joshy, and Nigel S. B. Rawson. 2024. “The impact of willingness-to-pay threshold on price reduction recommendations for oncology drugs: a review of assessments conducted by the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health.” Journal of Comparative Effectiveness Research 13: p. e230178. Available at

Binder, Louise, Majd Ghadban, Christina Sit, and Kathleen Barnard. 2022. “Health technology assessment process for oncology drugs: impact of CADTH changes on public payer reimbursement recommendations.” Current Oncology 29: pp. 1514–26. Available at

Bobrovitz, Niklas, Carl Heneghan, Igho Onakpoya, Benjamin Fletcher, Dylan Collins, Alice Tompson, Joseph Lee, David Nunan, Rebecca Fisher, Brittney Scott, Jack O’Sullivan, Oliver Van Hecke, Brian D. Nicholson, Sarah Stevens, Nia Roberts, and Kamal R. Mahtani. 2018. “Medications that reduce emergency hospital admissions: an overview of systematic reviews and prioritization of treatments.” BMC Medicine 16: p. 115. Available at

CDA. 2024. Procedures for reimbursement reviews. Ottawa: CDA September. Available at

CDA. 2025. Find reports. Ottawa: Canada’s Drug Agency. Available at

CHPI. 2024. “Waiting for new medicines in Canada, Europe, and the United States 2018–2023.” Canadian Health Policy, April. Available at

Corbella, Licia. 2022. “Canada’s health system overrun by administrators and lacks doctors.” Calgary Herald, January 24, 2022. Available at

Darke, Andrew C. 2023. “Can I be honest with my neurologist? A problem of health technology in Canada.” Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences Nov 8: pp. 1–3. Available at

Duong, Diana, and Lauren Vogel. 2023. “National survey highlights worsening primary care access.” Canadian Medical Association Journal 195: pp. E592–3. Available at

Fashami, Fatemeh M., Jean-Eric Tarride, Behnam Sadeghirad, Kimia Hariri, Amirreza Peyrovinasab, and Mitchell Levine. 2024. “Health technology assessment reports for non-oncology medications in Canada from 2018 to 2022: methodological critiques on manufacturers’ submissions and a comparison between manufacturer and Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH) analyses.” PharmacoEconomics Open 8: pp. 823–36. Available at

Government of Canada, 2024. Draft guidelines for PMPRB staff. Ottawa: Government of Canada, December. Available at

Grosse, Scott D. 2008. “Assessing cost-effectiveness in healthcare: history of the $50,000 per QALY threshold.” Expert Review of Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research 8: pp. 165–78. Available at

Health Canada. 2023. Government of Canada announces appointment to the Patented Medicine Prices Review Board. Ottawa: Government of Canada, February 1, 2023. Available at

Hofmann, Bjorn. 2013. Health technology assessment – science or art? GMS Health Technol Assess 9: p. Doc08. Available at:

Kirkey, Sharon. 2024. “’I don’t think I’ll last’: how Canada’s emergency room crisis could be killing thousands.” National Post, July 19, 2024. Available at

KPMG. 2023. Financial statements of Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health; year ended March 31, 2023. Canada’s Drug Agency. Available at

Lau, Robin S., Mari E. Boesen, Lawrence Richer, and Michael D. Hill. 2024. “Siloed mentality, health system suboptimization and the healthcare symphony: a Canadian Perspective.” Health Research Policy and Systems 22: p. 87. Available at

Lepage, Suzanne. 2024. “Navigating the challenges of drug management: tackling risk management, access and sustainability.” Benefits Canada. Available at

Lepage, Suzanne, and Carolyne Eagan. 2024. “Sounding board: what plan sponsors should know about pharmacare.” Benefits Canada, June 27, 2024. Available at

Moir, Mackenzie, and Bacchus Barua. 2023. “Waiting your turn: wait times for health care in Canada, 2023 report.” Vancouver: Fraser Institute. Available at

National Council on Disability. 2019. Quality-adjusted life years and the devaluation of life with disability. Washington, DC: National Council on Disability. Available at

Patient Voice, 2023. “Stories from the frontlines of the fight for access to innovative therapies.” Maclean’s August 3, 2023. Available at

pCPA, 2023. pCPA brand process guidelines. Available at

pCPA. 2025. Brand name drug negotiations status. pan-Canadian Pharmaceutical Alliance. Available at

Pettitt, David A., S. Raza, B. Naughton, A. Roscoe, A. Ramakrishnan, A. Ali, B. Davies, S. Dopson, G. Hollander, J.A. Smith, and D. A. Brindley. 2016. “The limitations of QALY: a literature review.” Journal of Stem Cell Research and Therapy 6: p. 4. Available at

Pyenson, Bruce, Rebecca Smith, Allison Halpren, and Parsa Entezarian. 2024. “A new framework for quantifying healthcare value using real-world evidence.” Millman Inc. Available at

Prieto, Luis, and José Sacristán. 2003. “Problems and solutions in calculating quality-adjusted life years (QALYs).” Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 1: p. 80. Available at

Rawson, Nigel S. B. 2001. “’Effectiveness’ in the evaluation of new drugs: a misunderstood concept?” Canadian Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 8: pp. 61–2.

Rawson, Nigel S. B. 2018. “Canadian, European and United States new drug approval times now relatively similar.” Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology 96: pp. 121–6. Available at

Rawson, Nigel S. B. 2021. “Health technology assessment standards and practices: how does Canada compare with other countries?” Canadian Health Policy, February 25, 2021. Available at

Rawson, Nigel S. B. 2022. “Health technology assessment and price negotiation alignment for rare disorder drugs in Canada: who benefits?” Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases 17: p. 218. Available at

Rawson, Nigel S. B., and John Adams. 2017. “Do reimbursement recommendation processes used by government drug plans in Canada adhere to good governance principles?” ClinicoEconomics and Outcomes Research 9: pp. 721–30. Available at

Rawson, Nigel, and John Adams. 2021. “Use COVID pause to reconsider drug-price regulation.” Ottawa: Macdonald-Laurier Institute, January 24, 2021. Available at

Rawson Nigel, and John Adams. 2023. “The drug prices review board was once a solution. It’s now a problem.” Financial Post, March 1, 2023. Available at

Rawson, Nigel, and John Adams. 2024. “Waiting for a new medicine? Unfortunately, that’s government policy across Canada.” The Hub, August 8, 2024. Available at

Rawson, Nigel, and John Adams. 2025. “One federal agency we could axe? The drug prices review board.” Financial Post, February 5, 2025. Available at

Rawson, Nigel S. B., and David J. Stewart. 2024. “Timeliness of health technology assessments and price negotiations for oncology drugs in Canada.” ClinicoEconomics and Outcomes Research 16: pp. 437–45. Available at

Richter, Trevor, Ghayath Janoudi, William Amegatse, and Sandra Nester-Parr. 2018. “Characteristics of drugs for ultra-rare diseases versus drugs for other rare diseases in HTA submissions made for the CADTH CDR.” Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases 13: p. 15. Available at

Rowen, Donna, Ismail Zouraq, Helene Chevrou-Severac, and Ben van Hout. 2017. “International regulations and recommendations for utility data for health technology assessment.” Pharmacoeconomics 35: pp. 11–19. Available at

Rushowy, Kristin. 2024. “Doug Ford wants Canada to approve drugs faster. Is that possible?” Toronto Star, July 15, 2024. Available at

Tam, Vincent C., Ravi Ramjeesingh, Ronald Burkes, Eric M. Yoshida, Sarah Doucette, and Howard J. Lim. 2022. “Emerging systemic therapies in advanced unresectable biliary tract cancer: review and Canadian perspective.” Current Oncology 29: pp. 7072–85. Available at

Zafar, Amina. 2024. “1 in 7 ER visits in Canada are for conditions that could have been managed in primary care: report.” CBC News, December 4, 2024. Available at