In director Kidar Sharma’s Chitralekha (1964), based on Bhagwati Charan Verma’s eponymous novel about the virtues and vices of human life, Bijgupt, a king, turns to the conscience and asks a pertinent question: “Man re, tu kaahe na dheer dhare? O nirmohi moh na jaane, jinka moh kare (Dear mind, why don’t you calm down? You don’t understand the worldly desires you try to seek)”.

Penned by lyricist Sahir Ludhianvi — who poured himself into this philosophical ditty while asking questions fraught with discomfort all the while finding the perfect median between a poem and a film song — the piece is a lesson in minimalism. Composed by Roshan in the profound raag Yaman, it was brought to life by Mohammed Rafi. “How much economy has he (Roshan) used in the tune? He knows the lyrics are good, the rendering will hold, and the piece does not need to be drowned in music. Only masters can do this. An ordinary music director wouldn’t know to just stop there,” says writer and lyricist Javed Akhtar about the song in The Roshans, a Netflix documentary on the composer and his family.

In the subjective world of music, where there is no perfect song, Man re’s uniqueness brings it quite close to the illusive concept. The piece isn’t a crafty rollercoaster, like many songs of that era based on ragas. Each note is carefully placed and somewhat an obvious fit. But upon its release, it did not cause much of a stir, neither on Binaca Geetmala — the countdown show that was the litmus test of a song’s popularity — nor among the masses. It didn’t help that the Pradeep Gupta and Meena Kumari-starrer flopped at the box office.

Looking back, it seems rather anomalous that the film’s music was not even nominated for a Filmfare award. The song that won in 1964 was Chahunga main tujhe saanjh saware (Dosti) created by Laxmikant-Pyarelal, winning over Madan Mohan’s Woh Kaun Thi and Shankar Jaikishan’s Sangam. Man re, however, remains one of the finest moments of not just Roshan’s extensive oeuvre but also of the delicacy of feeling and mental high ground that he, Ludhianvi and Rafi left us with. Last week, Roshan was given the Lifetime Achievement Award for his contribution to Hindi cinema at the 25th International Indian Film Academy Awards (IIFA) in Jaipur.

The award is also a reminder of Roshan’s body of work that includes the 11-song magnum opus Barsaat Ki Raat (1960), with some of the finest qawwalis of Hindi cinema; the complicated classic that is Laaga chunari mein daag (Dil Hi Toh Hai, 1963); and the sonic brilliance of Taj Mahal, 1963. In fact, so synonymous was the moniker Roshan with melodious music and a certain standard of composition that his first name eventually became a cultural force, adopted as his family name by his sons Rakesh and Rajesh and grandson Hrithik.

Also Read | The Roshans review: A valuable addition to films about Hindi film industry

Born in 1917 as Roshan Lal Nagrath in Pakistan’s Gujranwala, the composer trained in music at Marris College (now Bhatkhande Sanskriti Vishwavidyalaya) in Lucknow and trained in sarod under Ustad Allauddin Khan. In 1940, he began working as an esraj player at All India Radio (AIR) but in 1948, he quit his job and moved to Mumbai and assisted composer and AIR producer Khawaja Khurshid Anwar. It was after a few months of struggle that he met producer-director Kidar Sharma who gave him the film Neki Aur Badi (1949) — the film and its songs tanked without a blip. Sharma bet on Roshan again, mainly because he needed work and Sharma knew of his competence. The gamble paid off as Bawre Nain (1950) was a huge hit musically and people would cock their ears to Rajkumari Dubey singing the delightful force of nature that was Sun bairi balam sach bol re, ibb kya hoga.

Story continues below this ad

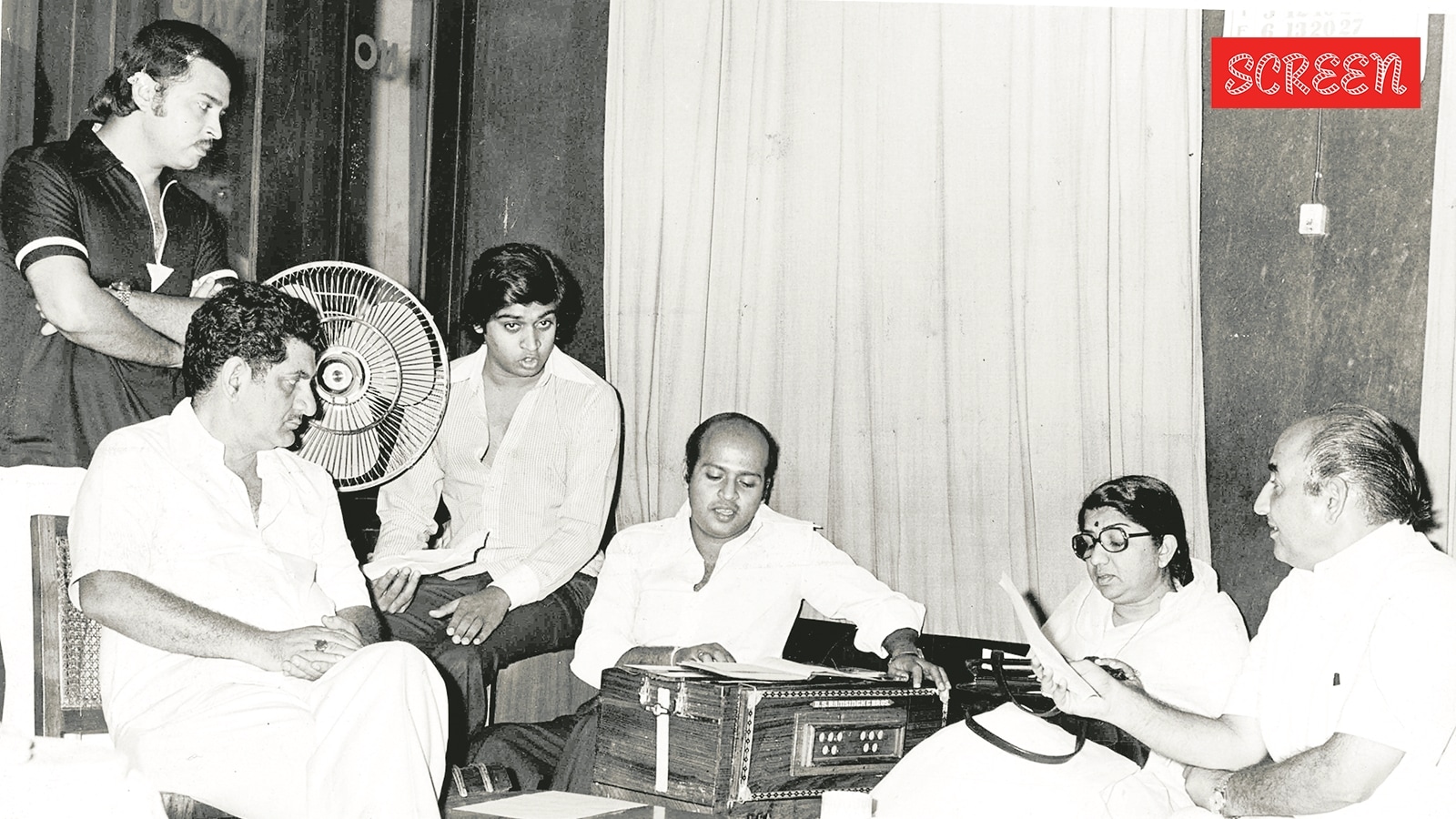

(From right) Mohd Rafi, Lata Mangeshkar, Roshan, Amit Kumar, Anand Bakshi, Rakesh Roshan

(From right) Mohd Rafi, Lata Mangeshkar, Roshan, Amit Kumar, Anand Bakshi, Rakesh Roshan

But what put Roshan on the map with contemporaries such as Shankar Jaikishan, Madan Mohan and Naushad, was Barsaat Ki Raat and its remarkable qawwali – Na toh karvaan ki talash hai, based on the tune Na toh butkade ki talab mujhe, sung by the Pakistani duo of Mubarak Ali Khan and Fateh Ali Khan (Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan’s uncle and father). Legend goes that Khayyam, who was asked by director R Chandra to compose for the film, refused to work with someone else’s composition. Roshan agreed. As he turned Na toh karvaan ki talaash hai into the epitome of the Hindi film qawwali — written by Sahir, with whom he had most of his hits — he also charmed the nation with the refrain Ye ishq ishq hai without sounding trite, despite the religious metaphors that followed. He created the gentle romance and whirling emotions in Zindagi bhar nahi bhoolegi wo barsaat ki raat, an ode to the silent meet-cute between Bharat Bhushan and Madhubala on a rain-soaked night.

Then there was the expansive Rahen na rahen hum (Mamta, 1966) which is inspired by SD Burman’s Thandi hawayein (Naujawan, 1951), the transience of life that was Taal mile nadi ke jal mein (Anokhi Raat, 1968) and Nigahen milaane ko jee chahta hai, Asha Bhosle’s qawwali. And who can forget the undying flare of Jo wada kiya wo nibhana padega (Taj Mahal). The latter is the only film for which Roshan won a Filmfare for Best Music Director. It remains the only award he won while he was alive. Roshan passed away at 50 due to a heart condition. The IIFA this month is a reminder of a composer whose tunes remain etched in memory not only for their technical rigour but also for a certain geniality and a balm for the wounds of the heart.

© The Indian Express Pvt Ltd