‘Colonialism is highly controversial in Canada…. But I am quite convinced that the prevailing narrative is so distorted as to be false’

Article content

A Vancouver theology school has cancelled a public lecture that was slated for next month by a renowned British historian over his views on Indian Residential Schools and colonialism.

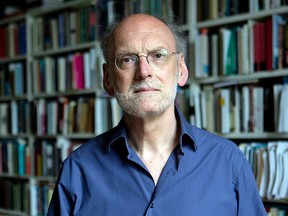

Esteemed ethicist and theologian Nigel Biggar — regius professor emeritus of moral and pastoral theology at the University of Oxford — now says he’s “ashamed to be an alumnus” of Regent College, which called off his March 6 lecture.

Advertisement 2

Article content

“I am aware, of course, that the topic of colonialism is highly controversial in Canada — as it is throughout the English-speaking world,” Biggar wrote in a recent note to Regent President Jeff Greenman after learning his talk had been cancelled.

“But I am quite convinced that the prevailing narrative is so distorted as to be false, as I have sought to show in my best-selling book, Colonialism: A Moral Reckoning.”

Greenman declined an interview request.

“I write to you regarding my decision last week not to proceed with the lecture by Dr. Nigel Biggar on ‘Colonialism Revisited: Did the British Empire Promote Human Welfare?’” Greenman wrote in a Feb. 14 note to Regent students.

“Such a sudden change naturally prompts questions about its rationale and so I wanted to share with you some of my thinking around the decision.”

The school is “committed to equipping students and encouraging our wider constituency ‘to engage their culture as thoughtful and prayerful Christians, sharing in Christ’s creative and redemptive mission,’” the president wrote. “That goal is pursued both inside the classroom and through various public events. In my judgment, the planned lecture on a very sensitive subject was not right for Regent since it needed different framing to foster constructive dialogue. Whenever we engage topics about which there is strong disagreement or controversy, it is critically important that all aspects of an event, from the choice of speaker to the event’s format, should demonstrate our concern for both critical reflection and appropriate pastoral awareness.”

Advertisement 3

Article content

In his note to students, Greenman said he realizes “that there will be disagreement about the decision I have made, and some will be disappointed or upset by this change of plans. I regret that the decision was not made before the lecture was announced.”

Biggar was invited last April to speak at Regent by Professor Jens Zimmermann, who also turned down an interview request this week.

I want the whole story to be told, not just part of it, and I want the record of British colonialism to be put in its proper context

In his correspondence with Greenman, Biggar chalks up the cancellation to “the intemperate, even abusive agitation that has recently appeared on the Regent alumni Facebook site. Again, let us be clear. These agitators were not protesting against being forced to listen to me, because no one was forcing them. No, they were protesting that Regent should allow anyone else to hear what I have to say, because they regard it not merely as mistaken but pernicious.”

In an interview this week, Biggar said he’s “never denied that European or British colonialism caused grief and harm to Indigenous peoples. But the British empire also chalked up some major humanitarian and liberal achievements. So, I want the whole story to be told, not just part of it, and I want the record of British colonialism to be put in its proper context, namely a world where, long before Europeans and Britons arrived in North America, North American peoples were in the business of dominating each other, sometimes enslaving each other.”

Article content

Advertisement 4

Article content

Biggar, who studied at Regent in the late 1970s, said he bears no personal resentment towards the college’s president.

“But I do object in the strongest possible terms to his decision, especially if that decision is expressive of a policy of repressing the responsible, rational criticism and discussion of prevailing views.”

On social media, Biggar has been dubbed “a residential school apologist” by another Regent alumnus.

“I’m someone who bases his views on evidence,” Biggar said.

“On the one hand, there is evidence that the conditions in residential schools was poor, that the mortality rates of Indian kids was unusually high, and there’s evidence that government funding was irresponsibly low. So, I’m not an apologist in the sense that I whitewash the record of the schools. However, it is now over three years since claims were made of the discovery of the mass graves of Indian kids who’d been murdered, and here we are three plus years later and not a single grave of a murdered kid has been discovered. So, my view is nuanced. On present evidence, I think there is no reason to suppose that mass murder took place in the schools.”

Advertisement 5

Article content

As late as the 1920s, “native communities in Alberta were asking for more schools of that kind,” he said. “So, the record is mixed.”

In his 2023 book on colonialism, Biggar writes of how “the schools were founded on a belief in a central racial equality and consequent faith in the capacity of native people to learn, adapt and develop.”

How does he square that with residential school survivors who say they were subjected to corporal punishment for speaking their own language?

“We all know that the best way to learn a foreign language is to be immersed in it,” Biggar said.

“Insofar as some schools forbade the kids to speak their own native languages it was with a view to facilitating their acquiring English language. As a matter of fact, there were certainly some schools where the encouragement to speak native languages was made outside the classroom. So, it’s not true to say that there was a general racist repression of the speaking of native languages by kids. As for corporal punishment … I went to a boarding school in England in the ‘60s. I was caned. It didn’t do me permanent damage.”

Advertisement 6

Article content

Aaron Pete, a councillor for Chawathil First Nation in B.C.’s Upper Fraser Valley, interviewed Biggar on his podcast, Bigger than me. He also plans to share the stage with the recent appointment to Britain’s House of Lords at a private event with a set guest list in Vancouver on March 4.

“Mr. Biggar and I do not agree on everything,” Pete said in an interview. “But I think it’s important that when we’re trying to reconcile history and when we’re trying to understand colonialism, and the idea of de-colonization, whatever that means, I think it’s important that we have … frank, difficult conversations so that we can … move forward in a more united way than we are.”

Recommended from Editorial

-

Peter Shawn Taylor: Colonialism contained ‘good things as well as bad.’ Why can’t we just accept that?

-

Terry Glavin: Residential school report — a 1,000-page dissertation in ‘settler colonialism’

The “unmarked graves story is controversial,” Pete said. “It’s creating further challenges for First Nations people, and we have to grapple with that.”

Detections from ground-penetrating radar “is evidence of something,” Pete said. “The point I hear from First Nations is we’re working on that and we’re trying to make decisions that are culturally appropriate for us. And that doesn’t pass the smell test for individuals like … Nigel Biggar.”

Advertisement 7

Article content

Biggar has also faced public criticism for his views on Britain’s role in the slave trade.

“Some Britons were involved in slave trading and slavery for about 150 years from 1650 to, roughly, 1800. I lament it. It was dreadful,” he said. “On the other hand, I admire the fact that other Britons, towards the end of the 1700s, began to agitate against slave trading and slavery, and that the British were amongst the first peoples in the history of the world to abolish both practices, and then to use imperial power worldwide to suppress other people’s slave trading and slavery, from Brazil to New Zealand. So, my view is, let’s tell the whole story.”

Biggar opposes reparations for slavery. “The present state of the descendants of slaves has been caused by all sorts of other factors other than the experience of slavery on the part of their ancestors two centuries ago.”

He points to “post-colonial mismanagement of the economies of let’s say Jamaica and some other Caribbean countries” as an example.

But isn’t it the case that African people wouldn’t have moved to the Caribbean en masse if it weren’t for the slave trade? “That’s true,” said Biggar, “and many of them would still be back in Nigeria.”

Advertisement 8

Article content

He points out that, according to the World Bank, “the gross national income per capita of the descendants of slaves in Barbados is 12 times higher than the gross national income per capita of Nigerians, many of whom are the descendants of slave owners and slave raiders. So, as it happens, fortunately, Barbadians are better off where they are than having stayed in Nigeria.”

Before his closed-door Vancouver lecture, Biggar is scheduled to appear publicly in Toronto March 1 for a conversation on colonialism with Margaret MacMillan, emeritus professor of history at the University of Toronto and Oxford. The event will be hosted by Canadian Institute for Historical Education. Postmedia, the company that owns National Post, is a media sponsor.

Biggar also plans to speak at inaugural meetings in both cities for the Free Speech Union of Canada.

Our website is the place for the latest breaking news, exclusive scoops, longreads and provocative commentary. Please bookmark nationalpost.com and sign up for our daily newsletter, Posted, here.

Article content