Simon & Schuster

We may receive an affiliate commission from anything you buy from this article.

British-born restaurateur Keith McNally was responsible for the opening of such popular New York City institutions as The Odeon, Balthazar and Pastis. But a 2016 stroke, which caused immobility and affected his speech, led him to attempt suicide two years later.

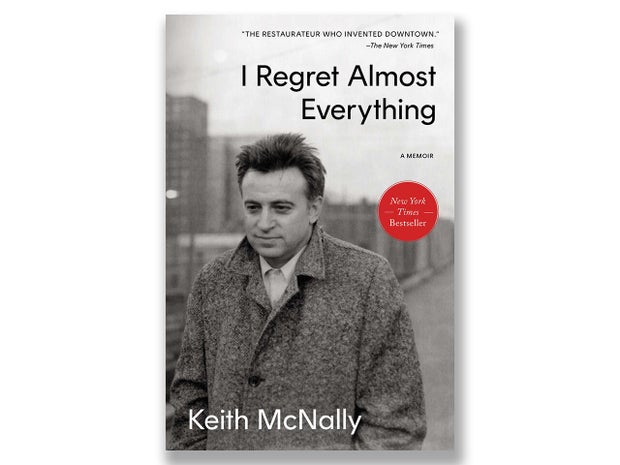

He’s recounted his story in the irreverent memoir “I Regret Almost Everything: A Memoir” (Simon & Schuster).

Read an excerpt below, and don’t miss Mo Rocca’s interview with Keith McNally on “CBS Sunday Morning” July 20!

“I Regret Almost Everything” by Keith McNally

Prefer to listen? Audible has a 30-day free trial available right now.

There was a time when everything worked. … I’d been happily married and the owner of eight successful Manhattan restaurants, including Balthazar in SoHo. In 2004, the New York Times had called me “The Restaurateur Who Invented Downtown.” I had everything going for me. And then on November 26, 2016, the clock stopped.

I was living in London. One Saturday morning I coaxed my youngest children, George and Alice, into seeing a Caravaggio exhibition with me at the National Gallery. George was thirteen, Alice eleven. While looking at a painting of Jesus being betrayed by Judas, The Taking of Christ, I sensed my body beginning to show signs of betraying me: a strange metallic tingling started to pinch my fingertips. It was an odd feeling, but as it stopped after five or six seconds, I didn’t give it another thought. Soon afterward, to the relief of my children, we left the museum.

Two hours later, when I was back home by myself, the metallic feeling returned. Only this time it was in earnest. Within seconds the horrific tingling shot up my left arm and, like some malignant jellyfish, clasped itself onto my face. Terrified, I phoned Alina, who rushed back with the kids and instantly called an ambulance. George, fists clenched, was panic-stricken as medics examined my convulsing body. Within minutes I was being hoisted into the waiting ambulance. Alina, George and Alice looked on.

I woke up several hours later in Charing Cross Hospital. The first thing the doctor told me was that I’d had a stroke. The second thing was that my brain would never be the same again. Perhaps his bluntness was necessary for legal reasons, but from where I stood—or lay—it was a brutal awakening.

After the doctor left, I tried wriggling my arms and legs to check that I wasn’t paralyzed. I wasn’t, thank God. To test my memory, I wrote the alphabet on the back of the nurse’s chart. I then tried saying the letters aloud, but here there was a problem. The words wouldn’t conform to my efforts. They exited my mouth in such a slurred and disorderly way that I sounded like a stage drunk. But this was a small price to pay for my stroke. My first stroke, that is. Because the next day the artillery arrived and gave me such a hammering that in one fell swoop I lost the use of my right hand, right arm and right leg. And my slurred speech, perhaps in fright, went AWOL. Overnight I was confined to a wheelchair and deprived of language.

So much for The Restaurateur Who Invented Downtown.

* * *

I shared a ward with five other men whose ages ranged from forty to eighty. At night, with words inaccessible to me, I’d listen in awe to them talking. Speech suddenly seemed like a divine accomplishment. Even everyday words had an element of poetry to them.

I dreaded the moment when the men would stop talking and I’d be left with my own thoughts. Sleepless, half-paralyzed and unable to speak, I felt buried alive. More than anything, I wished the stroke had killed me.

Bereft of speech and right side unusable, I wondered how my relationship with Alina might change. And with George and Alice also. All children exaggerate their father’s strength. Most sense it ebbing away imperceptibly over twenty or so years. Generally, a father’s decline appears natural, tolerable even. It wasn’t going to be like that for my children.

My new life seemed ungraspable. It existed, but was outside of me.

On my second day in the hospital, Alina arranged for George and Alice to visit. An hour before they were due, I became so ashamed of them seeing me disabled that I canceled the visit. The next day I could hold out no longer.

Hospitals are a great leveler. Like soldiers at war, patients lose all distinctiveness. As they entered the ward, George and Alice failed to recognize me. I was lying at the end of a row of identical beds, assimilating into the world of the sick and dying. Although it had only been three days since I last saw them, they looked years younger. They stood by the door, small eyes darting from one sick man to the next, searching for some identifiable sign of their father. After a few seconds they rushed to my bed.

Alice seemed happy to see me, but George looked angry and said less than usual. He’d behaved in a similar way a year earlier after watching me lose a match in a squash tournament. Back then, I found his anger confusing. Now it made sense.

Alina put on a brave face but was so shell-shocked she said little. I managed to gurgle out a few words, and in between the long silences the heavy breathing of the man in the next bed entered uncomfortably into our space. Alina told the children I was going to regain my voice and would soon be walking out of the hospital.

Neither responded.

When the three of them left, I wept for the first time in twenty years.

From “I Regret Almost Everything” by Keith McNally. Copyright © 2025 by Keith McNally. Excerpted with permission by Simon & Schuster, a division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Get the book here:

“I Regret Almost Everything” by Keith McNally

Buy locally from Bookshop.org

For more info: